Windows of the mus·ing - Communism/thinking & value 10.The Communist Manifesto 共産黨宣言

Windows of the mus·ing - Communism/thinking & value 10.The Communist Manifesto

共産黨宣言

《공산당 선언》(共産黨 宣言, 독일어: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei )은 공산주의 사상가인 카를 마르크스와 프리드리히 엥겔스에 의하여 집필된 공산주의자들의 최초의 강령적 문헌으로, 1848년 2월 21일 첫 출판되었다.

19세기 중엽 독자적인 정치 세력으로 무대에 등장한 프롤레타리아에게 그의 역사적 사명과 해방의 앞길을 밝혀 주고 국제공산주의운동의 지도적 지침을 확립한다는 목적의식 하에 1847년 마르크스와 엥겔스에 의하여 초안이 작성되었다. 1847년 마르크스와 엥겔스가 가입한 의인동맹(義人同盟, Bund der Gerechten)은 공산당선언을 동맹의 정책문서로 채택하였다. 그 해 여름 조직은 재정비되었고 1848년 공산주의자동맹으로 다시 태어났다.

선언은 생산 방식이 사회 제도의 성격을 규정하며 정치와 사회적 사상의식의 기초로 된다는 유물사관의 원리가 천명되어 있으며 자본주의사회의 기본 모순, 자본주의 멸망의 불가피성과 사회주의, 공산주의 승리의 필연성을 주장하고 있다는 이해도 있지만, 마르크스는 불가피성과 필연성에 대해서 이야기 하지 않았다. 그는 역사에 개입함으로써 변혁을 꾀할 여지가 있다고 믿었다. 그래서 자본주의가 모순을 가지고 나락으로 향하지만 그것자체만으로는 자동적으로 사회주의나 사회주의 이후의 공산주의로의 이행이 진행되지 않는다고 말했다. 즉 마르크스주의를 표현할 때 필연성이나 불가피성이라는 단어를 쓰는 것은 피상적인 이해에서 비롯된 것이라고 볼 수밖에 없다.

이 강령은 프롤레타리아 혁명을 포함하여 무계급 사회를 겨냥한 일련의 행동을 권장하였다. 이는 러시아를 비롯한 동유럽, 남미 등의 사회주의 운동의 기초가 되었다.

본 시리즈는 할머니, 할아버지들도 아시게끔 하고자 하는 의도가 포함되었다.

할머니, 할아버지의 정의 : 일반 대중들, 공무원 국장급 이하, 일반기업체 과장급 이하의 삶을 살아온 60세 이상의 시골사람들.

모든 주문에 적용되어지는 그림들은, 地球人 標準體, 地球人 標準流體를 適用하는 것으로 處理規律되었다.이는 플레이아데스 規律第1條, ANA-PLEIADES규율제1조로서 처리규율되었다.

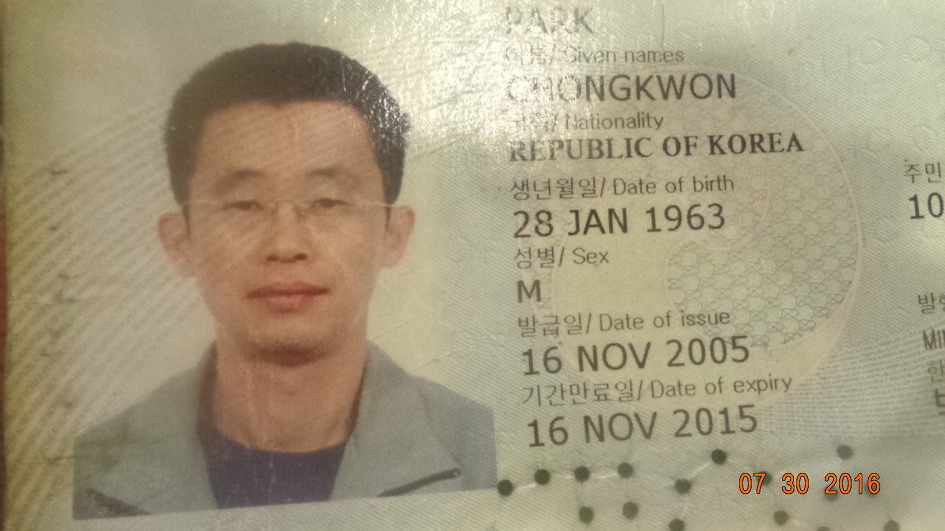

元本來的地球人的朴鐘權을 위하여, 純金 80kg(1次 : 30kg, 2次 : 50kg)을 보냈음에도 불구하고 1次 30kg은 大統領 박정희가 가로채었으며, 2차 50kg은 도무지 소식이 없으므로, 이에 대하여 플레이아데스 聯邦 檢察廳에 告訴處理規律되었다. 관련자 전원을 중벌에 처하도록 처리규율되었으며, 大統領의 地位에 있는 자로서, 말을 한 것에 대하여 지키지 아니하는 사람들에 대해서도, 太陽系的靈團 및 關聯檢察廳에 告訴處理規律되었다.이에 重罰에 처하는 것으로 處理規律되었다.BYTHEANA-PLEIADESTHESUPREMEBEINGS, BYTHEPLEIADESTHESUPREMEBEINGS的.

우리는 學問的體系를 基盤으로 이 글을 적는 것이 아니며, 지나간 55년간의 人生 속에서 얻어지는 經驗들과 그를 통한 思想을 글로서 적는 것으로 處理規律되었다.이는 ANA-PLEIADES規律第1條, 플레이아데스규율제1조로서 處理規律되었다.

The Communist Manifesto (originally Manifesto of the Communist Party) is an 1848 political pamphlet by the German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London (in German as Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei) just as the Revolutions of 1848 began to erupt, the Manifesto was later recognised as one of the world's most influential political documents. It presents an analytical approach to the class struggle (historical and then-present) and the conflicts of capitalism and the capitalist mode of production, rather than a prediction of communism's potential future forms.

The Communist Manifesto summarises Marx and Engels' theories concerning the nature of society and politics, namely that in their own words "[t]he history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". It also briefly features their ideas for how the capitalist society of the time would eventually be replaced by socialism. Near the end of the Manifesto, the authors call for a "forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions", which served as the justification for all communist revolutions around the world. In 2013, The Communist Manifesto was registered to UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme along with Marx's Capital, Volume I.[1]

경제적 이해관계의 대립에 기초한 피착취계급과 착취계급의 계급 투쟁이 인류 역사의 기본 내용이며 사회발전의 추동력이라 주장했다. 마르크스는 1장에서 부르주아가 이룬 막대한 업적을 역설적으로 찬양하였으나, 선언이 쓰여진 시점에서 부르주아는 "명계에서 불러낸 마물을 통제하지 못하게 된 마법사"와 같이 자본의 노예가 되었다고 비판한다. 그리고 지배계급도 부르주아지가 아닌 새롭게 떠오른 노동자,프롤레타리아 계급이 주역이 된 새로운 사회의 건설이 필요함을 역설했다.

Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") is a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting. In a direct democracy, the citizens as a whole form a governing body and vote directly on each issue. In a representative democracy the citizens elect representatives from among themselves. These representatives meet to form a governing body, such as a legislature. In a constitutional democracy the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority, usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech, or freedom of association.[1][2] "Rule of the majority" is sometimes referred to as democracy.[3] Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

According to American political scientist Larry Diamond, democracy consists of four key elements: a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; protection of the human rights of all citizens; a rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens.[5] Todd Landman, nevertheless, draws our attention to the fact that democracy and human rights are two different concepts and that "there must be greater specificity in the conceptualisation and operationalization of democracy and human rights".[6]

The term appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Athens, to mean "rule of the people", in contrast to aristocracy (ἀριστοκρατία, aristokratía), meaning "rule of an elite". While theoretically these definitions are in opposition, in practice the distinction has been blurred historically.[7] The political system of Classical Athens, for example, granted democratic citizenship to free men and excluded slaves and women from political participation. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship consisted of an elite class, until full enfranchisement was won for all adult citizens in most modern democracies through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in an absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy. Nevertheless, these oppositions, inherited from Greek philosophy,[8] are now ambiguous because contemporary governments have mixed democratic, oligarchic and monarchic elements. Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, thus focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution.[9]

-> 共産主義者들이 宗敎는 아편이다 라고 주장한 내용의 일부로서, 종교적 특성(기독교적 특성이며, 이는 그리스로마 시대의 종교적 특성과 대별된다)상, 부르주아지적 특성을 元本來的 기반으로 하기에, 사회주의라는 단어 자체가 부적절하므로 그렇게 말한 것으로 생각되었다. 그리스 로마시대의 종교는, 人間과 함께하는 神들의 형태가 심볼화되어 있다.

-> 現代의 대부분의 자본주의 국가인 미국, 영국, 일본, 한국등이 채택하고 있는 資本主義로서, 이를 부르주아적 사회주의로 규정한 내용이였다. 그러나 우리가 아는 바와 같이 허다한 문제들이 그대로 존속하며, 대부분은, 僞僞形되어진 封建王朝制, 貴族制度의 또 다른 변형체들에 불과하였다. 이에 대해서 우리는, 資本主義를 병행 공부함으로서, 할머니들의 이해를 돕고자 하였다.

부르주아지적 사회주의 형태를 취하는 현대자본주의의 한 단면을 보여주었다. 불과 8대그룹의 오너들(재벌총수그룹)이 一國의 富의 31%를 점유하는 不公正의 極端을 보이고 있었다. 현대자본주의 국가들이 이런 저런 개선책을 내놓고, 무언가 개선된 것처럼 속이고 있지만, 칼 마르크스는 이미 오래전부터 모든 사실적 진실들을 정확하게 보고 있었다.

The Communist Manifesto is divided into a preamble and four sections, the last of these a short conclusion. The introduction begins by proclaiming: "A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre". Pointing out that parties everywhere—including those in government and those in the opposition—have flung the "branding reproach of communism" at each other, the authors infer from this that the powers-that-be acknowledge communism to be a power in itself. Subsequently, the introduction exhorts Communists to openly publish their views and aims, to "meet this nursery tale of the spectre of communism with a manifesto of the party itself".

The first section of the Manifesto, "Bourgeois and Proletarians", elucidates the materialist conception of history, that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". Societies have always taken the form of an oppressed majority exploited under the yoke of an oppressive minority. In capitalism, the industrial working class, or proletariat, engage in class struggle against the owners of the means of production, the bourgeoisie. As before, this struggle will end in a revolution that restructures society, or the "common ruin of the contending classes". The bourgeoisie, through the "constant revolutionising of production [and] uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions" have emerged as the supreme class in society, displacing all the old powers of feudalism. The bourgeoisie constantly exploits the proletariat for its labour power, creating profit for themselves and accumulating capital. However, in doing so the bourgeoisie serves as "its own grave-diggers"; the proletariat inevitably will become conscious of their own potential and rise to power through revolution, overthrowing the bourgeoisie.

"Proletarians and Communists", the second section, starts by stating the relationship of conscious communists to the rest of the working class. The communists' party will not oppose other working-class parties, but unlike them, it will express the general will and defend the common interests of the world's proletariat as a whole, independent of all nationalities. The section goes on to defend communism from various objections, including claims that it advocates communal prostitution or disincentivises people from working. The section ends by outlining a set of short-term demands—among them a progressive income tax; abolition of inheritances and private property; abolition of child labour; free public education; nationalisation of the means of transport and communication; centralisation of credit via a national bank; expansion of publicly owned etc.—the implementation of which would result in the precursor to a stateless and classless society.

The third section, "Socialist and Communist Literature", distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time—these being broadly categorised as Reactionary Socialism; Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism; and Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism. While the degree of reproach toward rival perspectives varies, all are dismissed for advocating reformism and failing to recognise the pre-eminent revolutionary role of the working class. "Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Opposition Parties", the concluding section of the Manifesto, briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the mid-nineteenth century such as France, Switzerland, Poland and Germany, this last being "on the eve of a bourgeois revolution" and predicts that a world revolution will soon follow. It ends by declaring an alliance with the democratic socialists, boldly supporting other communist revolutions and calling for united international proletarian action—"Working Men of All Countries, Unite!".

민주주의(民主主義, 영어: democracy)는 國家의 主權이 國民에게 있고 國民이 勸力을 가지고 그 勸力을 스스로 行事하며 國民을 위하여 政治를 행하는 制度, 또는 그러한 정치를 지향하는 사상이다. 민주주의(democracy)라는 용어는 고대 그리스어 dêmos(인민)과 krátos(힘)의 합성어 dēmokratía에서 나왔다.

Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") is a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting. In a direct democracy, the citizens as a whole form a governing body and vote directly on each issue. In a representative democracy the citizens elect representatives from among themselves. These representatives meet to form a governing body, such as a legislature. In a constitutional democracy the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority, usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech, or freedom of association.[1][2] "Rule of the majority" is sometimes referred to as democracy.[3] Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

민주주의는 의사결정 시 시민권이 있는 대다수나 모두에게 열린 선거나 국민 정책투표를 이용하여 전체에 걸친 구성원의 의사를 반영하고 실현하는 사상이나 정치사회 체제이다. '국민이 주권을 행사하는 이념과 체제'라고도 일반으로 표현된다.

'민주주의'는 근대사회에서 서구의 자유민주주의나 사회민주주의와 동의어처럼 사용되었으나 반자유주의 성격을 띤 민주주의 정체를 도입한 국가도 분명히 있는 맥락에서 수식어인 '자유주의'는 엄밀히 말하면, 입헌주의 성격을 띤 자유주의와 개인의 평등한 인권 보장을 지칭하나 민주주의는 다른 견해로도 기술된다.

어느 때든, 민주주의 사상이 사회와 정치 문화에 대한 합리적 여러 견해를 포괄하는 것으로 그 뜻이 널리 확장될 수 있다. 민주주의를 다룬 가장 간결한 정의로는, 에이브러햄 링컨이 게티즈버그 연설에서 한 연설의 한 대목인 "국민의, 국민에 의한 국민을 위한 정부"가 된다. 이는 민주주의의 핵심 요소로 국민주권과 국민자치 중 평등주의를 포함한다

-> 일반적으로는 資本主義 國家에 대해서, 自由民主主義 혹은 民主主義 體制라는 單語를 사용하는데, 共産社會主義, 共産主義에 대해서는 보통 民主主義라는 單語를 사용하지 않는 것이 통례였다. 그러나 우리가 보건대는, 資本主義 體制下에서의 "민주주의"란, 다만, 정치관련하여 투표권이 있다는 것 외에는 아무런 의미가 없는 虛像的 거짓이며, 僞僞形的 封建君主制를 擁護하기 위한 거짓에 불과하였다. 즉, 자본주의 체제하에서의 민주주의란 "政治的 民主主義"를 意味하였다.

그러나 대다수 사람들의 삶을 통제하는 것은, 政治가 아니며, 經濟라는 점을 우리는 모두 認識하고 있었다. 資本主義 體制는, 民主主義를 僞裝한, 經濟獨裁主義라고 定義될 수도 있었다. -> 經濟獨裁主義에 대해서도 우리는 向後 工夫할 豫程이었다.

상기 도표에서 볼수 있듯이, 共産社會主義 體制國家의 牽制로 인하여, 1950년~1980년까지의 미국경제는 經濟正義가 실현되는 듯 보여지고 있었지만, 고르바초프의 改革과 開放以後의 蘇聯의 沒落은, 또 다시 과거의 惡德資本主義의 惡夢을 되살리고 있었다고 생각되었다. 이는 共産社會主義로 인하여, 資本主義 體制가 좋아진 것을 意味하였다.

냉전(冷戰, 문화어: 랭전, 영어: Cold War, 러시아어: Холо́дная война)은 제2차 세계 대전 이후부터 1991년까지 미국과 소비에트 연방을 비롯한 양측 동맹국 사이에서 갈등, 긴장, 경쟁 상태가 이어진 대립 시기를 말한다. '냉전'이라는 표현은 버나드 바루크가 1947년에 트루먼 독트린에 관한 논쟁 중 이 말을 써서 유명해졌는데, 이것은 무기를 들고 싸운다는 의미의 전쟁인 열전(熱戰, 영어: hot war)과 다르다. 당시에 냉전 주축 국가의 군대가 직접 서로 충돌한 적은 없었으나, 두 세력은 군사 동맹, 재래식 군대의 전략적 배치, 핵무기, 군비 경쟁, 첩보전, 대리전(proxy war), 선전, 그리고 우주 진출과 같은 기술 개발 경쟁의 양상을 보이며 서로 대립하였다.

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the Soviet Union with its satellite states (the Eastern Bloc), and the United States with its allies (the Western Bloc) after World War II. A common historiography of the conflict begins with 1946, the year U.S. diplomat George F. Kennan's "Long Telegram" from Moscow cemented a U.S. foreign policy of containment of Soviet expansionism threatening strategically vital regions, and ending between the Revolutions of 1989 and the 1991 collapse of the USSR, which ended communism in Eastern Europe. The term "cold" is used because there was no large-scale fighting directly between the two sides, but they each supported major regional conflicts known as proxy wars.

的的及的的徧的的浹的的李健熙的的及的的徧的的浹的的庶子的的及的的徧的的浹的的이서현的的及的的徧的的浹的的洪羅喜的的及的的徧的的浹的的李在鎔的的及的的徧的的浹的的李健熙的的及的的徧的的浹的的無條件的的及的的徧的的浹的的殺害的的及的的徧的的浹的的除去的的及的的徧的的浹的的消滅的的及的的徧的的浹的的持續的的及的的徧的的浹的的處理的的及的的徧的的浹的的恒久的的及的的徧的的浹的的處理的的及的的徧的的浹的的永久的的及的的徧的的浹的的處理的的及的的徧的的浹的的永遠的的及的的徧的的浹的的處理的的及的的徧的的浹的的무한(無限) 반복(反復)的的及的的徧的的浹的的處理的的及的的徧的的浹的的諸一切的的及的的徧的的浹的的ether醚的的及的的徧的的浹的的體的的及的的徧的的浹的的無關係的的及的的徧的的浹的的dependence (up)on的的及的的徧的的浹的的Pleiades的的及的的徧的的浹的的su·preme的的及的的徧的的浹的的being的的及的的徧的的浹的的Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") is a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting. In a direct democracy, the citizens as a whole form a governing body and vote directly on each issue. In a representative democracy the citizens elect representatives from among themselves. These representatives meet to form a governing body, such as a legislature. In a constitutional democracy the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority, usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech, or freedom of association.[1][2] "Rule of the majority" is sometimes referred to as democracy.[3] Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

According to American political scientist Larry Diamond, democracy consists of four key elements: a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; protection of the human rights of all citizens; a rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens.[5] Todd Landman, nevertheless, draws our attention to the fact that democracy and human rights are two different concepts and that "there must be greater specificity in the conceptualisation and operationalization of democracy and human rights".[6]

The term appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Athens, to mean "rule of the people", in contrast to aristocracy (ἀριστοκρατία, aristokratía), meaning "rule of an elite". While theoretically these definitions are in opposition, in practice the distinction has been blurred historically.[7] The political system of Classical Athens, for example, granted democratic citizenship to free men and excluded slaves and women from political participation. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship consisted of an elite class, until full enfranchisement was won for all adult citizens in most modern democracies through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in an absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy. Nevertheless, these oppositions, inherited from Greek philosophy,[8] are now ambiguous because contemporary governments have mixed democratic, oligarchic and monarchic elements. Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, thus focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution.[

A republic (Latin: res publica) is a form of government in which the country is considered a “public matter”, not the private concern or property of the rulers. The primary positions of power within a republic are not inherited, but are attained through democracy, oligarchy or autocracy. It is a form of government under which the head of state is not a hereditary monarch.[1][2][3]

In the context of American constitutional law, the definition of republic refers specifically to a form of government in which elected individuals represent the citizen body[2][better source needed] and exercise power according to the rule of law under a constitution, including separation of powers with an elected head of state, referred to as a constitutional republic[4][5][6][7] or representative democracy.[8]

As of 2017[update], 159 of the world’s 206 sovereign states use the word “republic” as part of their official names – not all of these are republics in the sense of having elected governments, nor is the word “republic” used in the names of all nations with elected governments. While heads of state often tend to claim that they rule only by the “consent of the governed”, elections in some countries have been found to be held more for the purpose of “show” than for the actual purpose of in reality providing citizens with any genuine ability to choose their own leaders.[9]

The word republic comes from the Latin term res publica, which literally means “public thing,” “public matter,” or “public affair” and was used to refer to the state as a whole. The term developed its modern meaning in reference to the constitution of the ancient Roman Republic, lasting from the overthrow of the kings in 509 B.C. to the establishment of the Empire in 27 B.C. This constitution was characterized by a Senate composed of wealthy aristocrats and wielding significant influence; several popular assemblies of all free citizens, possessing the power to elect magistrates and pass laws; and a series of magistracies with varying types of civil and political authority.

Most often a republic is a single sovereign state, but there are also sub-sovereign state entities that are referred to as republics, or that have governments that are described as “republican” in nature. For instance, Article IV of the United States Constitution "guarantee[s] to every State in this Union a Republican form of Government".[10] In contrast, the former Soviet Union, which described itself as being a group of “Republics” and also as a “federal multinational state composed of 15 republics”, was widely viewed as being a totalitarian form of government and not a genuine republic, since its electoral system was structured so as to automatically guarantee the election of government-sponsored candidates.[

The term originates from the Latin translation of Greek word politeia. Cicero, among other Latin writers, translated politeia as res publica and it was in turn translated by Renaissance scholars as "republic" (or similar terms in various western European languages).[citation needed]

The term politeia can be translated as form of government, polity, or regime and is therefore not always a word for a specific type of regime as the modern word republic is. One of Plato's major works on political science was titled Politeia and in English it is thus known as The Republic. However, apart from the title, in modern translations of The Republic, alternative translations of politeia are also used.[12]

However, in Book III of his Politics, Aristotle was apparently the first classical writer to state that the term politeia can be used to refer more specifically to one type of politeia: "When the citizens at large govern for the public good, it is called by the name common to all governments (to koinon onoma pasōn tōn politeiōn), government (politeia)". Also amongst classical Latin, the term "republic" can be used in a general way to refer to any regime, or in a specific way to refer to governments which work for the public good.[13]

In medieval Northern Italy, a number of city states had commune or signoria based governments. In the late Middle Ages, writers such as Giovanni Villani began writing about the nature of these states and the differences from other types of regime. They used terms such as libertas populi, a free people, to describe the states. The terminology changed in the 15th century as the renewed interest in the writings of Ancient Rome caused writers to prefer using classical terminology. To describe non-monarchical states writers, most importantly Leonardo Bruni, adopted the Latin phrase res publica.[14]

While Bruni and Machiavelli used the term to describe the states of Northern Italy, which were not monarchies, the term res publica has a set of interrelated meanings in the original Latin. The term can quite literally be translated as "public matter".[15] It was most often used by Roman writers to refer to the state and government, even during the period of the Roman Empire.[16]

In subsequent centuries, the English word "commonwealth" came to be used as a translation of res publica, and its use in English was comparable to how the Romans used the term res publica.[17] Notably, during The Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell the word commonwealth was the most common term to call the new monarchless state, but the word republic was also in common use.[18] Likewise, in Polish the term was translated as rzeczpospolita, although the translation is now only used with respect to Poland.

Presently, the term "republic" commonly means a system of government which derives its power from the people rather than from another basis, such as heredity or divine right.[

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit.[1][2][3][4] Characteristics central to capitalism include private property, capital accumulation, wage labor, voluntary exchange, a price system, and competitive markets.[5][6] In a capitalist market economy, decision-making and investment are determined by every owner of wealth, property or production ability in financial and capital markets, whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.[7][8]

Economists, political economists, sociologists and historians have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include laissez-faire or free market capitalism, welfare capitalism and state capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership,[9] obstacles to free competition and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets, the role of intervention and regulation, and the scope of state ownership vary across different models of capitalism.[10][11] The extent to which different markets are free as well as the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most existing capitalist economies are mixed economies, which combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.[12]

Market economies have existed under many forms of government and in many different times, places and cultures. Modern capitalist societies—marked by a universalization of money-based social relations, a consistently large and system-wide class of workers who must work for wages, and a capitalist class which owns the means of production—developed in Western Europe in a process that led to the Industrial Revolution. Capitalist systems with varying degrees of direct government intervention have since become dominant in the Western world and continue to spread. Over time, capitalist countries have experienced consistent economic growth and an increase in the standard of living.

Critics of capitalism argue that it establishes power in the hands of a minority capitalist class that exists through the exploitation of the majority working class and their labor; prioritizes profit over social good, natural resources and the environment; and is an engine of inequality, corruption and economic instabilities. Supporters argue that it provides better products and innovation through competition, disperses wealth to all productive people, promotes pluralism and decentralization of power, creates strong economic growth, and yields productivity and prosperity that greatly benefit society

The term "capitalist", meaning an owner of capital, appears earlier than the term "capitalism" and it dates back to the mid-17th century. "Capitalism" is derived from capital, which evolved from capitale, a late Latin word based on caput, meaning "head"—also the origin of "chattel" and "cattle" in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). Capitale emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries in the sense of referring to funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money or money carrying interest.[24]:232[25][26] By 1283, it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm and it was frequently interchanged with a number of other words—wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.[24]:233

The Hollandische Mercurius uses "capitalists" in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital.[24]:234 In French, Étienne Clavier referred to capitalistes in 1788,[27] six years before its first recorded English usage by Arthur Young in his work Travels in France (1792).[26][28] In his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), David Ricardo referred to "the capitalist" many times.[29] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, an English poet, used "capitalist" in his work Table Talk (1823).[30] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon used the term "capitalist" in his first work, What is Property? (1840), to refer to the owners of capital. Benjamin Disraeli used the term "capitalist" in his 1845 work Sybil.[26]

The initial usage of the term "capitalism" in its modern sense has been attributed to Louis Blanc in 1850 ("What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others") and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861 ("Economic and social regime in which capital, the source of income, does not generally belong to those who make it work through their labour").[24]:237 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels referred to the "capitalistic system"[31][32] and to the "capitalist mode of production" in Capital (1867).[33] The use of the word "capitalism" in reference to an economic system appears twice in Volume I of Capital, p. 124 (German edition) and in Theories of Surplus Value, tome II, p. 493 (German edition). Marx did not extensively use the form capitalism, but instead those of capitalist and capitalist mode of production, which appear more than 2,600 times in the trilogy The Capital. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the term "capitalism" first appeared in English in 1854 in the novel The Newcomes by novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, where he meant "having ownership of capital".[34] Also according to the OED, Carl Adolph Douai, a German American socialist and abolitionist, used the phrase "private capitalism" in 1863.

The rule of law is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as: "The authority and influence of law in society, especially when viewed as a constraint on individual and institutional behavior; (hence) the principle whereby all members of a society (including those in government) are considered equally subject to publicly disclosed legal codes and processes."[2] The phrase "the rule of law" refers to a political situation, not to any specific legal rule.

Use of the phrase can be traced to 16th-century Britain, and in the following century the Scottish theologian Samuel Rutherford employed it in arguing against the divine right of kings.[3] John Locke wrote that freedom in society means being subject only to laws made by a legislature that apply to everyone, with a person being otherwise free from both governmental and private restrictions upon liberty. "The rule of law" was further popularized in the 19th century by British jurist A. V. Dicey. However, the principle, if not the phrase itself, was recognized by ancient thinkers; for example, Aristotle wrote: "It is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens".[4]

The rule of law implies that every person is subject to the law, including people who are lawmakers, law enforcement officials, and judges.[5] In this sense, it stands in contrast to a monarchy or oligarchy where the rulers are held above the law.[citation needed] Lack of the rule of law can be found in both democracies and monarchies, for example, because of neglect or ignorance of the law, and the rule of law is more apt to decay if a government has insufficient corrective mechanisms for restoring it.

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct.[1] The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns matters of value, and thus comprises the branch of philosophy called axiology.[2]

Ethics seeks to resolve questions of human morality by defining concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime. As a field of intellectual inquiry, moral philosophy also is related to the fields of moral psychology, descriptive ethics, and value theory.

Three major areas of study within ethics recognized today are:[1]

觀自在菩薩 行深般若波羅蜜多時 照見五蘊皆空 度一切苦厄

관자재보살(관세음보살)이 반야바라밀다(부처님의 지혜)를 행할때 오온이 모두 비어 있음을 비추어 보시고 하나이자 전부인 온갖 괴로움과 재앙을 건넜다.

舍利子 色不異空 空不異色 色卽是空 空卽是色 受想行識 亦復如是

사리자여, 물질이 공(空)과 다르지 않고 공이 물질과 다르지 않으며 물질이 곧 공이요, 공이 곧 물질이다. 느낌, 생각과 지어감, 의식 또한 그러하니라.

舍利子 是諸法空相 不生不滅 不垢不淨 不增不減

사리자여, 이 모든 법은 나지도 않고 멸하지도 않으며, 더럽지도 않고 깨끗하지도 않으며, 늘지도 줄지도 않느니라

是故 空中無色無受想行識 無眼耳鼻舌身意 無色聲香味觸法 無眼界 乃至 無意識界

그러므로 공 가운데는 색이 없고 수 상 행 식도 없으며, 안이비설신의도 없고, 색성향미촉법도 없으며, 눈의 경계도 의식의 경계까지도 없으며

無無明 亦無無明盡 乃至 無老死 亦無老死盡

무명도 무명이 다함까지도 없으며, 늙고 죽음도 늙고 죽음이 다함까지도 없고

無苦集滅道 無智 亦無得 以無所得故 菩提薩陀 依般若波羅蜜多

고집멸도도 없으며, 지혜도 얻음도 없느리라. 얻을것이 없는 까닭에 보살은 반야바라밀다를 의지하므로

故心無罣碍 無罣碍故 無有恐怖 遠離 (一切) 顚倒夢想 究竟涅槃

마음에 걸림이 없고, 걸림이 없으므로 두려움이 없어서 뒤바뀐 헛된 생각을 멀리 떠나 완전한 열반에 들어가며

三世諸佛依般若波羅蜜多 故得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提 故知般若波羅蜜多 是大神呪 是大明呪 是無上呪 是無等等呪 能除一切苦 眞實不虛

삼세의 모든 부처님도 이 반야바라밀다를 의지하므로 최상의 깨달음을 얻느니라. 반야바라밀다는 가장 신비하고 밝은 주문이며, 위없는 주문이며, 무엇과도 견줄 수 없는 주문이니, 온갖 괴로움을 없애고 진실하여 허망하지 않음을 알지니라.

故說般若波羅蜜多呪 卽說呪曰

이제 반야바라밀다주를 말하리라.

揭諦揭諦 波羅揭諦 波羅僧揭諦 菩提 娑婆訶(3)

'아제아제 바라아제 바라승아제 모지 사바하'(3)

(Gate Gate paragate parasamgate Bodhi Svaha:가테 가테 파라가테 파라삼가테 보디 스바하)

가자, 가자, 피안(彼岸)으로 가자, 피안으로 넘어가자, 영원한 깨달음이여的的及的的遍的的民主主義的的及的的遍的的

共産黨宣言

《공산당 선언》(共産黨 宣言, 독일어: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei )은 공산주의 사상가인 카를 마르크스와 프리드리히 엥겔스에 의하여 집필된 공산주의자들의 최초의 강령적 문헌으로, 1848년 2월 21일 첫 출판되었다.

19세기 중엽 독자적인 정치 세력으로 무대에 등장한 프롤레타리아에게 그의 역사적 사명과 해방의 앞길을 밝혀 주고 국제공산주의운동의 지도적 지침을 확립한다는 목적의식 하에 1847년 마르크스와 엥겔스에 의하여 초안이 작성되었다. 1847년 마르크스와 엥겔스가 가입한 의인동맹(義人同盟, Bund der Gerechten)은 공산당선언을 동맹의 정책문서로 채택하였다. 그 해 여름 조직은 재정비되었고 1848년 공산주의자동맹으로 다시 태어났다.

선언은 생산 방식이 사회 제도의 성격을 규정하며 정치와 사회적 사상의식의 기초로 된다는 유물사관의 원리가 천명되어 있으며 자본주의사회의 기본 모순, 자본주의 멸망의 불가피성과 사회주의, 공산주의 승리의 필연성을 주장하고 있다는 이해도 있지만, 마르크스는 불가피성과 필연성에 대해서 이야기 하지 않았다. 그는 역사에 개입함으로써 변혁을 꾀할 여지가 있다고 믿었다. 그래서 자본주의가 모순을 가지고 나락으로 향하지만 그것자체만으로는 자동적으로 사회주의나 사회주의 이후의 공산주의로의 이행이 진행되지 않는다고 말했다. 즉 마르크스주의를 표현할 때 필연성이나 불가피성이라는 단어를 쓰는 것은 피상적인 이해에서 비롯된 것이라고 볼 수밖에 없다.

이 강령은 프롤레타리아 혁명을 포함하여 무계급 사회를 겨냥한 일련의 행동을 권장하였다. 이는 러시아를 비롯한 동유럽, 남미 등의 사회주의 운동의 기초가 되었다.

본 시리즈는 할머니, 할아버지들도 아시게끔 하고자 하는 의도가 포함되었다.

落水效果

朝鮮時代의 食事文化중 재미있는 것은, 고을원님의 식사광경이었다. 누군가에게 들은 이야기인데, 식사시간이 되면, 고을원님이 먼저 한상 차려서 식사하시고, 상을 물리면, 그 상을 차례로 계급별로 물림하여 먹고 내리고, 먹고 내리고 하여 맨 마지막에는, 하인들까지 내려갔다고 하였다. 이것은, 현대자본주의체제에서도 동일한데, 그래서, 大統領이라는 사람들이 즐겨 쓰는 單語가 바로 落水效果였다. 經濟體制가 改善되지 아니하는 理由중 하나는, 이른바 統治權者들이 한통속이기 때문이었고, 칼 마르크스는 이러한 점을 잘 인식하고 있었다.

오늘의 단원정리

共産主義 思想은, 우리가 흔히 알던 바와 같이, 급진적이고 억압적이며 통제적이고, 불온 불순하며 악마적 사상과 가치체계는 아니었다는 점을 배웠다.

共産主義는, 萬民平等思想에 基礎되어지는 思想的 價値體系였다.

共産主義, 共産社會主義의 급진적 강제적 강압적 통제방식과 혁명적 철학사상들은, 부르조아지적 특성이 어디에 있는지를 잘 알기에 그러한 방식을 취한 것으로 생각되었다.

The Communist Manifesto (originally Manifesto of the Communist Party) is an 1848 political pamphlet by the German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London (in German as Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei) just as the Revolutions of 1848 began to erupt, the Manifesto was later recognised as one of the world's most influential political documents. It presents an analytical approach to the class struggle (historical and then-present) and the conflicts of capitalism and the capitalist mode of production, rather than a prediction of communism's potential future forms.

The Communist Manifesto summarises Marx and Engels' theories concerning the nature of society and politics, namely that in their own words "[t]he history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". It also briefly features their ideas for how the capitalist society of the time would eventually be replaced by socialism. Near the end of the Manifesto, the authors call for a "forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions", which served as the justification for all communist revolutions around the world. In 2013, The Communist Manifesto was registered to UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme along with Marx's Capital, Volume I.[1]

1장[편집]

제1장 〈부르주아지와 프롤레타리아트〉에서 마르크스와 엥겔스는 자본주의 생산방식의 발생 과정, 자본주의적 착취의 본질, 자본주의의 기본 모순과 그 멸망의 불가피성을 설명하였으며경제적 이해관계의 대립에 기초한 피착취계급과 착취계급의 계급 투쟁이 인류 역사의 기본 내용이며 사회발전의 추동력이라 주장했다. 마르크스는 1장에서 부르주아가 이룬 막대한 업적을 역설적으로 찬양하였으나, 선언이 쓰여진 시점에서 부르주아는 "명계에서 불러낸 마물을 통제하지 못하게 된 마법사"와 같이 자본의 노예가 되었다고 비판한다. 그리고 지배계급도 부르주아지가 아닌 새롭게 떠오른 노동자,프롤레타리아 계급이 주역이 된 새로운 사회의 건설이 필요함을 역설했다.

Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") is a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting. In a direct democracy, the citizens as a whole form a governing body and vote directly on each issue. In a representative democracy the citizens elect representatives from among themselves. These representatives meet to form a governing body, such as a legislature. In a constitutional democracy the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority, usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech, or freedom of association.[1][2] "Rule of the majority" is sometimes referred to as democracy.[3] Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

According to American political scientist Larry Diamond, democracy consists of four key elements: a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; protection of the human rights of all citizens; a rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens.[5] Todd Landman, nevertheless, draws our attention to the fact that democracy and human rights are two different concepts and that "there must be greater specificity in the conceptualisation and operationalization of democracy and human rights".[6]

The term appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Athens, to mean "rule of the people", in contrast to aristocracy (ἀριστοκρατία, aristokratía), meaning "rule of an elite". While theoretically these definitions are in opposition, in practice the distinction has been blurred historically.[7] The political system of Classical Athens, for example, granted democratic citizenship to free men and excluded slaves and women from political participation. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship consisted of an elite class, until full enfranchisement was won for all adult citizens in most modern democracies through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in an absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy. Nevertheless, these oppositions, inherited from Greek philosophy,[8] are now ambiguous because contemporary governments have mixed democratic, oligarchic and monarchic elements. Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, thus focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution.[9]

2장[편집]

제2장 〈프롤레타리아와 공산주의자〉에서 마르크스와 엥겔스는 선언의 이 부분에서 공산주의자들의 당면 과업이 프롤레타리아의 목적과 일치한다고 주장하며 프롤레타리아 주도의 공산사회를 만드는 것이 모든 공산주의자들의 최고목적이라고 밝혔다.3장[편집]

제3장 〈사회주의 문헌과 공산주의 문헌〉에서는 기독교 사회주의,유토피아 사회주의 등의 기존의 사이비적 사회주의 조류들을 비판하였다.사이비 사회주의 논박[편집]

그가 논박한 사회주의의 조류는 크게 나누면 기독교 사회주의, 봉건적 사회주의, 부르주아 사회주의 또는 보수적 사회주의, 사변적 사회주의이다.기독교 사회주의[편집]

기독교 사회주의는 기독교의 무소유 사상을 강조한 것으로 사회주의처럼 보일 뿐이다. 봉건적 사회주의에서 논의됨.-> 共産主義者들이 宗敎는 아편이다 라고 주장한 내용의 일부로서, 종교적 특성(기독교적 특성이며, 이는 그리스로마 시대의 종교적 특성과 대별된다)상, 부르주아지적 특성을 元本來的 기반으로 하기에, 사회주의라는 단어 자체가 부적절하므로 그렇게 말한 것으로 생각되었다. 그리스 로마시대의 종교는, 人間과 함께하는 神들의 형태가 심볼화되어 있다.

봉건적 사회주의[편집]

봉건적 사회주의는 부르주아에 의해 주류에서 밀려난 귀족계급이 부르주아들에게 착취당하는 노동자들에게 우호적 모습을 보임으로써 부르주아를 공격하는 것이다. 물론 봉건적 사회주의의 목적은 귀족들이 민중들을 지배하던 '좋았던 옛날'로 돌아가는 것이다. 그래서 마르크스는 귀족들이 노동자들에게 동정적 모습으로 다가서지만 노동자들은 귀족의 문장을 보고 돌아선다고 말했다.부르주아적 사회주의[편집]

부르주아적 사회주의 또는 보수적 사회주의는 사회문제들을 개선함으로써 자본주의를 유지하려는 개량주의이다. 근대 복음주의자들에게서 볼 수 있는 기독교 인도주의가 여기에 해당하는데, 이들은 노예제 반대운동, 노동자들의 노동시간을 제한한 공장법 입법등을 주장했지만, 정작 노동운동을 통해 인권과 평등을 주장하고 실천하려는 민중운동을 두려워했다.[1]-> 現代의 대부분의 자본주의 국가인 미국, 영국, 일본, 한국등이 채택하고 있는 資本主義로서, 이를 부르주아적 사회주의로 규정한 내용이였다. 그러나 우리가 아는 바와 같이 허다한 문제들이 그대로 존속하며, 대부분은, 僞僞形되어진 封建王朝制, 貴族制度의 또 다른 변형체들에 불과하였다. 이에 대해서 우리는, 資本主義를 병행 공부함으로서, 할머니들의 이해를 돕고자 하였다.

부르주아지적 사회주의 형태를 취하는 현대자본주의의 한 단면을 보여주었다. 불과 8대그룹의 오너들(재벌총수그룹)이 一國의 富의 31%를 점유하는 不公正의 極端을 보이고 있었다. 현대자본주의 국가들이 이런 저런 개선책을 내놓고, 무언가 개선된 것처럼 속이고 있지만, 칼 마르크스는 이미 오래전부터 모든 사실적 진실들을 정확하게 보고 있었다.

사변적 사회주의[편집]

사변적 사회주의는 사회주의 이론이 정립되기이전이라 현실을 무시한 이론에 그치던 유럽 사회주의를 가리킨다.[2]제4장[편집]

제4장 〈각종 반정부당에 대한 공산주의자들의 태도〉에서는 각국 공산당들의 기본적인 혁명 전략을 다루고 있다. 선언은 국제적 단결의 중요성을 강조하는 "공산주의 혁명에서 프롤레타리아가 잃을 것은 족쇄뿐이고 그들이 얻을 것은 전 세계이다. 전 세계 노동자들이여, 단결하라!"라는 구호로 끝을 맺는다.The Communist Manifesto is divided into a preamble and four sections, the last of these a short conclusion. The introduction begins by proclaiming: "A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre". Pointing out that parties everywhere—including those in government and those in the opposition—have flung the "branding reproach of communism" at each other, the authors infer from this that the powers-that-be acknowledge communism to be a power in itself. Subsequently, the introduction exhorts Communists to openly publish their views and aims, to "meet this nursery tale of the spectre of communism with a manifesto of the party itself".

The first section of the Manifesto, "Bourgeois and Proletarians", elucidates the materialist conception of history, that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". Societies have always taken the form of an oppressed majority exploited under the yoke of an oppressive minority. In capitalism, the industrial working class, or proletariat, engage in class struggle against the owners of the means of production, the bourgeoisie. As before, this struggle will end in a revolution that restructures society, or the "common ruin of the contending classes". The bourgeoisie, through the "constant revolutionising of production [and] uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions" have emerged as the supreme class in society, displacing all the old powers of feudalism. The bourgeoisie constantly exploits the proletariat for its labour power, creating profit for themselves and accumulating capital. However, in doing so the bourgeoisie serves as "its own grave-diggers"; the proletariat inevitably will become conscious of their own potential and rise to power through revolution, overthrowing the bourgeoisie.

"Proletarians and Communists", the second section, starts by stating the relationship of conscious communists to the rest of the working class. The communists' party will not oppose other working-class parties, but unlike them, it will express the general will and defend the common interests of the world's proletariat as a whole, independent of all nationalities. The section goes on to defend communism from various objections, including claims that it advocates communal prostitution or disincentivises people from working. The section ends by outlining a set of short-term demands—among them a progressive income tax; abolition of inheritances and private property; abolition of child labour; free public education; nationalisation of the means of transport and communication; centralisation of credit via a national bank; expansion of publicly owned etc.—the implementation of which would result in the precursor to a stateless and classless society.

The third section, "Socialist and Communist Literature", distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time—these being broadly categorised as Reactionary Socialism; Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism; and Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism. While the degree of reproach toward rival perspectives varies, all are dismissed for advocating reformism and failing to recognise the pre-eminent revolutionary role of the working class. "Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Opposition Parties", the concluding section of the Manifesto, briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the mid-nineteenth century such as France, Switzerland, Poland and Germany, this last being "on the eve of a bourgeois revolution" and predicts that a world revolution will soon follow. It ends by declaring an alliance with the democratic socialists, boldly supporting other communist revolutions and calling for united international proletarian action—"Working Men of All Countries, Unite!".

민주주의(民主主義, 영어: democracy)는 國家의 主權이 國民에게 있고 國民이 勸力을 가지고 그 勸力을 스스로 行事하며 國民을 위하여 政治를 행하는 制度, 또는 그러한 정치를 지향하는 사상이다. 민주주의(democracy)라는 용어는 고대 그리스어 dêmos(인민)과 krátos(힘)의 합성어 dēmokratía에서 나왔다.

Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") is a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting. In a direct democracy, the citizens as a whole form a governing body and vote directly on each issue. In a representative democracy the citizens elect representatives from among themselves. These representatives meet to form a governing body, such as a legislature. In a constitutional democracy the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority, usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech, or freedom of association.[1][2] "Rule of the majority" is sometimes referred to as democracy.[3] Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

민주주의는 의사결정 시 시민권이 있는 대다수나 모두에게 열린 선거나 국민 정책투표를 이용하여 전체에 걸친 구성원의 의사를 반영하고 실현하는 사상이나 정치사회 체제이다. '국민이 주권을 행사하는 이념과 체제'라고도 일반으로 표현된다.

'민주주의'는 근대사회에서 서구의 자유민주주의나 사회민주주의와 동의어처럼 사용되었으나 반자유주의 성격을 띤 민주주의 정체를 도입한 국가도 분명히 있는 맥락에서 수식어인 '자유주의'는 엄밀히 말하면, 입헌주의 성격을 띤 자유주의와 개인의 평등한 인권 보장을 지칭하나 민주주의는 다른 견해로도 기술된다.

어느 때든, 민주주의 사상이 사회와 정치 문화에 대한 합리적 여러 견해를 포괄하는 것으로 그 뜻이 널리 확장될 수 있다. 민주주의를 다룬 가장 간결한 정의로는, 에이브러햄 링컨이 게티즈버그 연설에서 한 연설의 한 대목인 "국민의, 국민에 의한 국민을 위한 정부"가 된다. 이는 민주주의의 핵심 요소로 국민주권과 국민자치 중 평등주의를 포함한다

-> 일반적으로는 資本主義 國家에 대해서, 自由民主主義 혹은 民主主義 體制라는 單語를 사용하는데, 共産社會主義, 共産主義에 대해서는 보통 民主主義라는 單語를 사용하지 않는 것이 통례였다. 그러나 우리가 보건대는, 資本主義 體制下에서의 "민주주의"란, 다만, 정치관련하여 투표권이 있다는 것 외에는 아무런 의미가 없는 虛像的 거짓이며, 僞僞形的 封建君主制를 擁護하기 위한 거짓에 불과하였다. 즉, 자본주의 체제하에서의 민주주의란 "政治的 民主主義"를 意味하였다.

그러나 대다수 사람들의 삶을 통제하는 것은, 政治가 아니며, 經濟라는 점을 우리는 모두 認識하고 있었다. 資本主義 體制는, 民主主義를 僞裝한, 經濟獨裁主義라고 定義될 수도 있었다. -> 經濟獨裁主義에 대해서도 우리는 向後 工夫할 豫程이었다.

상기 도표에서 볼수 있듯이, 共産社會主義 體制國家의 牽制로 인하여, 1950년~1980년까지의 미국경제는 經濟正義가 실현되는 듯 보여지고 있었지만, 고르바초프의 改革과 開放以後의 蘇聯의 沒落은, 또 다시 과거의 惡德資本主義의 惡夢을 되살리고 있었다고 생각되었다. 이는 共産社會主義로 인하여, 資本主義 體制가 좋아진 것을 意味하였다.

냉전(冷戰, 문화어: 랭전, 영어: Cold War, 러시아어: Холо́дная война)은 제2차 세계 대전 이후부터 1991년까지 미국과 소비에트 연방을 비롯한 양측 동맹국 사이에서 갈등, 긴장, 경쟁 상태가 이어진 대립 시기를 말한다. '냉전'이라는 표현은 버나드 바루크가 1947년에 트루먼 독트린에 관한 논쟁 중 이 말을 써서 유명해졌는데, 이것은 무기를 들고 싸운다는 의미의 전쟁인 열전(熱戰, 영어: hot war)과 다르다. 당시에 냉전 주축 국가의 군대가 직접 서로 충돌한 적은 없었으나, 두 세력은 군사 동맹, 재래식 군대의 전략적 배치, 핵무기, 군비 경쟁, 첩보전, 대리전(proxy war), 선전, 그리고 우주 진출과 같은 기술 개발 경쟁의 양상을 보이며 서로 대립하였다.

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the Soviet Union with its satellite states (the Eastern Bloc), and the United States with its allies (the Western Bloc) after World War II. A common historiography of the conflict begins with 1946, the year U.S. diplomat George F. Kennan's "Long Telegram" from Moscow cemented a U.S. foreign policy of containment of Soviet expansionism threatening strategically vital regions, and ending between the Revolutions of 1989 and the 1991 collapse of the USSR, which ended communism in Eastern Europe. The term "cold" is used because there was no large-scale fighting directly between the two sides, but they each supported major regional conflicts known as proxy wars.

사회주의(社會主義, Socialism)는 생산 수단의 사적 소유와 소수 관리에 반대하고 공동체주의와 최대 다수의 행복 실현을 최고 가치로 하는 공동 이익 인간관[1] 을 사회 또는 윤리관의 기반으로 삼고[2][3] 자원을 효율적으로 분배하며 생산수단을 공동으로 운영하는 협동 경제와 모든 민중이 노동의 대가로서 정당하고 평등하게 분배받는 사회를 지향하는 다양한 사상을 통틀어 일컫는 말이며, 또는 그 과정을 의미하기도 한다. 사회적 소유는 국가, 집단 또는 협동조합의 소유 또는 지분을 시민이 소유하는 형태가 될 수도 있다. 다양한 형태의 사회주의가 존재하며, 사회적 소유라는 공통요소를 공유할 뿐 모든 형태를 포괄하는 한 가지 정의는 없다. 정치적으로 강력하게 등장한 근대적 사회주의인 초기 사회주의는 1826년 최초로 로버트 오언에 의해 주장되었지만, 훨씬 이전인 고대 그리스의 철학자 플라톤에서부터 사회주의와 밀접한 사상이 생겨났었으며, 생시몽의 공동체주의, 토머스 모어의 기독교 평등 사상이 생겨났다. 로버트 오언은 '사회주의'란 용어를 정립화했고, 그 후 유럽 각지에서 푸리에같은 여러 공동체, 집산주의를 지향하며, 이상적인 사회를 꿈꾸는 진보적 학자들에 의해 사회주의는 발전되었다. 오늘날, 사회주의는 민주사회주의나 공산주의와 같은 뜻으로 치환되기도 한다

초기 사회주의자들은 자본주의가 다음과 같은 문제를 내포한다고 여겼다. 자본을 쥐고 착취를 통해 부를 축적한 사회의 극소수에게 권력과 부가 집중되어, 모든 사람이 자신의 가능성을 펼칠 수 있는 평등한 기회를 부여받지 못하고[22], 기술과 자원의 이용이 제한당하며[23], 자본주의적 소유관계가 생산력에 족쇄를 채운다[24] 는 것이다.

-> 經濟力 集中은 獨占, 獨寡占의 弊害와 더불어서, 新規進入 自體가 애초에 不可能하게 만들고 있었다. 인간의 모든 속성이 그렇듯, 한번 움켜쥔 權力의 단맛은 결코 놓칠수 없는 것이었다. 자본주의적 소유관계가 생산력에 족쇄를 채운다는 의미는, "극소수 자본가들에게만 돈이 집중되므로, 즉 부가 집중되므로, 대다수 사람들의 호주머니는 가볍게 되며, 그로 인하여 소요량이 제한되는 현상을 의미하는 것으로 생각되었다. 돈이 있어야 물건을 사지? 즉, 所要量이 있다면 生産은 아무런 문제가 없는데도 불구하고 소요량이 제한된다는 의미로서 解釋되었다.

칼 마르크스의 공산주의 이론은 매우 옳았다.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

According to American political scientist Larry Diamond, democracy consists of four key elements: a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; protection of the human rights of all citizens; a rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens.[5] Todd Landman, nevertheless, draws our attention to the fact that democracy and human rights are two different concepts and that "there must be greater specificity in the conceptualisation and operationalization of democracy and human rights".[6]

The term appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Athens, to mean "rule of the people", in contrast to aristocracy (ἀριστοκρατία, aristokratía), meaning "rule of an elite". While theoretically these definitions are in opposition, in practice the distinction has been blurred historically.[7] The political system of Classical Athens, for example, granted democratic citizenship to free men and excluded slaves and women from political participation. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship consisted of an elite class, until full enfranchisement was won for all adult citizens in most modern democracies through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in an absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy. Nevertheless, these oppositions, inherited from Greek philosophy,[8] are now ambiguous because contemporary governments have mixed democratic, oligarchic and monarchic elements. Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, thus focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution.[

A republic (Latin: res publica) is a form of government in which the country is considered a “public matter”, not the private concern or property of the rulers. The primary positions of power within a republic are not inherited, but are attained through democracy, oligarchy or autocracy. It is a form of government under which the head of state is not a hereditary monarch.[1][2][3]

In the context of American constitutional law, the definition of republic refers specifically to a form of government in which elected individuals represent the citizen body[2][better source needed] and exercise power according to the rule of law under a constitution, including separation of powers with an elected head of state, referred to as a constitutional republic[4][5][6][7] or representative democracy.[8]

As of 2017[update], 159 of the world’s 206 sovereign states use the word “republic” as part of their official names – not all of these are republics in the sense of having elected governments, nor is the word “republic” used in the names of all nations with elected governments. While heads of state often tend to claim that they rule only by the “consent of the governed”, elections in some countries have been found to be held more for the purpose of “show” than for the actual purpose of in reality providing citizens with any genuine ability to choose their own leaders.[9]

The word republic comes from the Latin term res publica, which literally means “public thing,” “public matter,” or “public affair” and was used to refer to the state as a whole. The term developed its modern meaning in reference to the constitution of the ancient Roman Republic, lasting from the overthrow of the kings in 509 B.C. to the establishment of the Empire in 27 B.C. This constitution was characterized by a Senate composed of wealthy aristocrats and wielding significant influence; several popular assemblies of all free citizens, possessing the power to elect magistrates and pass laws; and a series of magistracies with varying types of civil and political authority.

Most often a republic is a single sovereign state, but there are also sub-sovereign state entities that are referred to as republics, or that have governments that are described as “republican” in nature. For instance, Article IV of the United States Constitution "guarantee[s] to every State in this Union a Republican form of Government".[10] In contrast, the former Soviet Union, which described itself as being a group of “Republics” and also as a “federal multinational state composed of 15 republics”, was widely viewed as being a totalitarian form of government and not a genuine republic, since its electoral system was structured so as to automatically guarantee the election of government-sponsored candidates.[

The term originates from the Latin translation of Greek word politeia. Cicero, among other Latin writers, translated politeia as res publica and it was in turn translated by Renaissance scholars as "republic" (or similar terms in various western European languages).[citation needed]

The term politeia can be translated as form of government, polity, or regime and is therefore not always a word for a specific type of regime as the modern word republic is. One of Plato's major works on political science was titled Politeia and in English it is thus known as The Republic. However, apart from the title, in modern translations of The Republic, alternative translations of politeia are also used.[12]

However, in Book III of his Politics, Aristotle was apparently the first classical writer to state that the term politeia can be used to refer more specifically to one type of politeia: "When the citizens at large govern for the public good, it is called by the name common to all governments (to koinon onoma pasōn tōn politeiōn), government (politeia)". Also amongst classical Latin, the term "republic" can be used in a general way to refer to any regime, or in a specific way to refer to governments which work for the public good.[13]

In medieval Northern Italy, a number of city states had commune or signoria based governments. In the late Middle Ages, writers such as Giovanni Villani began writing about the nature of these states and the differences from other types of regime. They used terms such as libertas populi, a free people, to describe the states. The terminology changed in the 15th century as the renewed interest in the writings of Ancient Rome caused writers to prefer using classical terminology. To describe non-monarchical states writers, most importantly Leonardo Bruni, adopted the Latin phrase res publica.[14]

While Bruni and Machiavelli used the term to describe the states of Northern Italy, which were not monarchies, the term res publica has a set of interrelated meanings in the original Latin. The term can quite literally be translated as "public matter".[15] It was most often used by Roman writers to refer to the state and government, even during the period of the Roman Empire.[16]

In subsequent centuries, the English word "commonwealth" came to be used as a translation of res publica, and its use in English was comparable to how the Romans used the term res publica.[17] Notably, during The Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell the word commonwealth was the most common term to call the new monarchless state, but the word republic was also in common use.[18] Likewise, in Polish the term was translated as rzeczpospolita, although the translation is now only used with respect to Poland.

Presently, the term "republic" commonly means a system of government which derives its power from the people rather than from another basis, such as heredity or divine right.[

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit.[1][2][3][4] Characteristics central to capitalism include private property, capital accumulation, wage labor, voluntary exchange, a price system, and competitive markets.[5][6] In a capitalist market economy, decision-making and investment are determined by every owner of wealth, property or production ability in financial and capital markets, whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.[7][8]

Economists, political economists, sociologists and historians have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include laissez-faire or free market capitalism, welfare capitalism and state capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership,[9] obstacles to free competition and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets, the role of intervention and regulation, and the scope of state ownership vary across different models of capitalism.[10][11] The extent to which different markets are free as well as the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most existing capitalist economies are mixed economies, which combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.[12]

Market economies have existed under many forms of government and in many different times, places and cultures. Modern capitalist societies—marked by a universalization of money-based social relations, a consistently large and system-wide class of workers who must work for wages, and a capitalist class which owns the means of production—developed in Western Europe in a process that led to the Industrial Revolution. Capitalist systems with varying degrees of direct government intervention have since become dominant in the Western world and continue to spread. Over time, capitalist countries have experienced consistent economic growth and an increase in the standard of living.

Critics of capitalism argue that it establishes power in the hands of a minority capitalist class that exists through the exploitation of the majority working class and their labor; prioritizes profit over social good, natural resources and the environment; and is an engine of inequality, corruption and economic instabilities. Supporters argue that it provides better products and innovation through competition, disperses wealth to all productive people, promotes pluralism and decentralization of power, creates strong economic growth, and yields productivity and prosperity that greatly benefit society

The term "capitalist", meaning an owner of capital, appears earlier than the term "capitalism" and it dates back to the mid-17th century. "Capitalism" is derived from capital, which evolved from capitale, a late Latin word based on caput, meaning "head"—also the origin of "chattel" and "cattle" in the sense of movable property (only much later to refer only to livestock). Capitale emerged in the 12th to 13th centuries in the sense of referring to funds, stock of merchandise, sum of money or money carrying interest.[24]:232[25][26] By 1283, it was used in the sense of the capital assets of a trading firm and it was frequently interchanged with a number of other words—wealth, money, funds, goods, assets, property and so on.[24]:233

The Hollandische Mercurius uses "capitalists" in 1633 and 1654 to refer to owners of capital.[24]:234 In French, Étienne Clavier referred to capitalistes in 1788,[27] six years before its first recorded English usage by Arthur Young in his work Travels in France (1792).[26][28] In his Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817), David Ricardo referred to "the capitalist" many times.[29] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, an English poet, used "capitalist" in his work Table Talk (1823).[30] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon used the term "capitalist" in his first work, What is Property? (1840), to refer to the owners of capital. Benjamin Disraeli used the term "capitalist" in his 1845 work Sybil.[26]

The initial usage of the term "capitalism" in its modern sense has been attributed to Louis Blanc in 1850 ("What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others") and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in 1861 ("Economic and social regime in which capital, the source of income, does not generally belong to those who make it work through their labour").[24]:237 Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels referred to the "capitalistic system"[31][32] and to the "capitalist mode of production" in Capital (1867).[33] The use of the word "capitalism" in reference to an economic system appears twice in Volume I of Capital, p. 124 (German edition) and in Theories of Surplus Value, tome II, p. 493 (German edition). Marx did not extensively use the form capitalism, but instead those of capitalist and capitalist mode of production, which appear more than 2,600 times in the trilogy The Capital. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the term "capitalism" first appeared in English in 1854 in the novel The Newcomes by novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, where he meant "having ownership of capital".[34] Also according to the OED, Carl Adolph Douai, a German American socialist and abolitionist, used the phrase "private capitalism" in 1863.

The rule of law is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as: "The authority and influence of law in society, especially when viewed as a constraint on individual and institutional behavior; (hence) the principle whereby all members of a society (including those in government) are considered equally subject to publicly disclosed legal codes and processes."[2] The phrase "the rule of law" refers to a political situation, not to any specific legal rule.

Use of the phrase can be traced to 16th-century Britain, and in the following century the Scottish theologian Samuel Rutherford employed it in arguing against the divine right of kings.[3] John Locke wrote that freedom in society means being subject only to laws made by a legislature that apply to everyone, with a person being otherwise free from both governmental and private restrictions upon liberty. "The rule of law" was further popularized in the 19th century by British jurist A. V. Dicey. However, the principle, if not the phrase itself, was recognized by ancient thinkers; for example, Aristotle wrote: "It is more proper that law should govern than any one of the citizens".[4]

The rule of law implies that every person is subject to the law, including people who are lawmakers, law enforcement officials, and judges.[5] In this sense, it stands in contrast to a monarchy or oligarchy where the rulers are held above the law.[citation needed] Lack of the rule of law can be found in both democracies and monarchies, for example, because of neglect or ignorance of the law, and the rule of law is more apt to decay if a government has insufficient corrective mechanisms for restoring it.

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong conduct.[1] The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns matters of value, and thus comprises the branch of philosophy called axiology.[2]

Ethics seeks to resolve questions of human morality by defining concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime. As a field of intellectual inquiry, moral philosophy also is related to the fields of moral psychology, descriptive ethics, and value theory.

Three major areas of study within ethics recognized today are:[1]

- Meta-ethics, concerning the theoretical meaning and reference of moral propositions, and how their truth values (if any) can be determined

- Normative ethics, concerning the practical means of determining a moral course of action

- Applied ethics, concerning what a person is obligated (or permitted) to do in a specific situation or a particular domain of action[1]

觀自在菩薩 行深般若波羅蜜多時 照見五蘊皆空 度一切苦厄

관자재보살(관세음보살)이 반야바라밀다(부처님의 지혜)를 행할때 오온이 모두 비어 있음을 비추어 보시고 하나이자 전부인 온갖 괴로움과 재앙을 건넜다.

舍利子 色不異空 空不異色 色卽是空 空卽是色 受想行識 亦復如是

사리자여, 물질이 공(空)과 다르지 않고 공이 물질과 다르지 않으며 물질이 곧 공이요, 공이 곧 물질이다. 느낌, 생각과 지어감, 의식 또한 그러하니라.

舍利子 是諸法空相 不生不滅 不垢不淨 不增不減

사리자여, 이 모든 법은 나지도 않고 멸하지도 않으며, 더럽지도 않고 깨끗하지도 않으며, 늘지도 줄지도 않느니라

是故 空中無色無受想行識 無眼耳鼻舌身意 無色聲香味觸法 無眼界 乃至 無意識界

그러므로 공 가운데는 색이 없고 수 상 행 식도 없으며, 안이비설신의도 없고, 색성향미촉법도 없으며, 눈의 경계도 의식의 경계까지도 없으며

無無明 亦無無明盡 乃至 無老死 亦無老死盡

무명도 무명이 다함까지도 없으며, 늙고 죽음도 늙고 죽음이 다함까지도 없고

無苦集滅道 無智 亦無得 以無所得故 菩提薩陀 依般若波羅蜜多

고집멸도도 없으며, 지혜도 얻음도 없느리라. 얻을것이 없는 까닭에 보살은 반야바라밀다를 의지하므로

故心無罣碍 無罣碍故 無有恐怖 遠離 (一切) 顚倒夢想 究竟涅槃

마음에 걸림이 없고, 걸림이 없으므로 두려움이 없어서 뒤바뀐 헛된 생각을 멀리 떠나 완전한 열반에 들어가며

三世諸佛依般若波羅蜜多 故得阿耨多羅三藐三菩提 故知般若波羅蜜多 是大神呪 是大明呪 是無上呪 是無等等呪 能除一切苦 眞實不虛

삼세의 모든 부처님도 이 반야바라밀다를 의지하므로 최상의 깨달음을 얻느니라. 반야바라밀다는 가장 신비하고 밝은 주문이며, 위없는 주문이며, 무엇과도 견줄 수 없는 주문이니, 온갖 괴로움을 없애고 진실하여 허망하지 않음을 알지니라.

故說般若波羅蜜多呪 卽說呪曰

이제 반야바라밀다주를 말하리라.

揭諦揭諦 波羅揭諦 波羅僧揭諦 菩提 娑婆訶(3)

'아제아제 바라아제 바라승아제 모지 사바하'(3)

(Gate Gate paragate parasamgate Bodhi Svaha:가테 가테 파라가테 파라삼가테 보디 스바하)

가자, 가자, 피안(彼岸)으로 가자, 피안으로 넘어가자, 영원한 깨달음이여的的及的的遍的的民主主義的的及的的遍的的

댓글

댓글 쓰기