Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") 2. - liberty (Latin: Libertas)

槐山郡的曾坪邑的及的曲江里的及的的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的

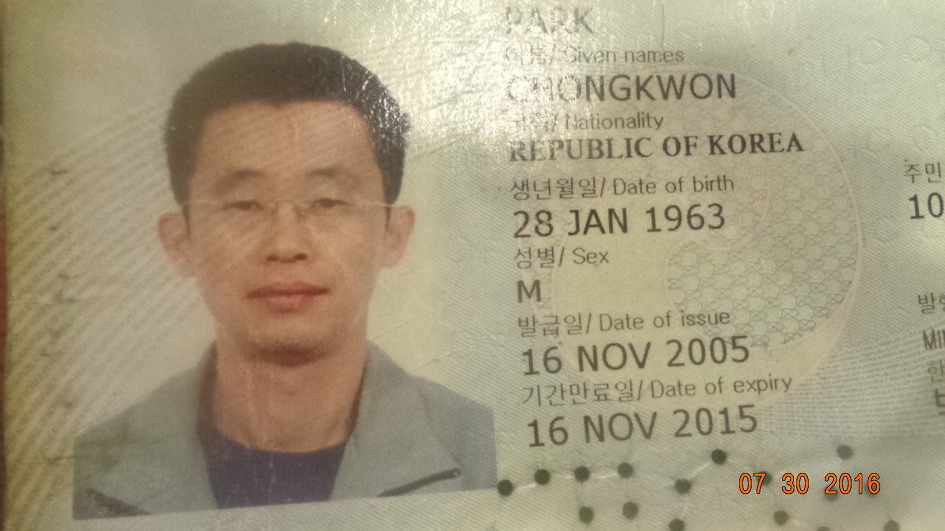

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的左側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的cognition的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Human rights的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Masculinity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的Femininity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Femininity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Femininity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Femininity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Femininity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Knowledge的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的Wisdom的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的personal identity的及的扱的浹的skill的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的左右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的左右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的左右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的左右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的左右側眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的左右側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的前後側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的family tree的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的上下側的及的扱的浹的眼的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子的及的扱的浹的性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子的及的扱的浹的性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子的及的扱的浹的性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子的及的扱的浹的性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子的及的扱的浹的性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子的及的扱的浹的性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的男子的及的扱的浹的性器的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屌的及的扱的浹的屪的及的扱的浹的㞗的及的扱的浹的娡的及的扱的浹的䘒的及的扱的浹的腎的及的扱的浹的肾的及的扱的浹的脧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屌的及的扱的浹的屪的及的扱的浹的㞗的及的扱的浹的娡的及的扱的浹的䘒的及的扱的浹的腎的及的扱的浹的肾的及的扱的浹的脧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屌的及的扱的浹的屪的及的扱的浹的㞗的及的扱的浹的娡的及的扱的浹的䘒的及的扱的浹的腎的及的扱的浹的肾的及的扱的浹的脧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屌的及的扱的浹的屪的及的扱的浹的㞗的及的扱的浹的娡的及的扱的浹的䘒的及的扱的浹的腎的及的扱的浹的肾的及的扱的浹的脧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屌的及的扱的浹的屪的及的扱的浹的㞗的及的扱的浹的娡的及的扱的浹的䘒的及的扱的浹的腎的及的扱的浹的肾的及的扱的浹的脧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屌的及的扱的浹的屪的及的扱的浹的㞗的及的扱的浹的娡的及的扱的浹的䘒的及的扱的浹的腎的及的扱的浹的肾的及的扱的浹的脧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屌的及的扱的浹的屪的及的扱的浹的㞗的及的扱的浹的娡的及的扱的浹的䘒的及的扱的浹的腎的及的扱的浹的肾的及的扱的浹的脧的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屄的及的扱的浹的毴的及的扱的浹的膣的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屄的及的扱的浹的毴的及的扱的浹的膣的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屄的及的扱的浹的毴的及的扱的浹的膣的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屄的及的扱的浹的毴的及的扱的浹的膣的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屄的及的扱的浹的毴的及的扱的浹的膣的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屄的及的扱的浹的毴的及的扱的浹的膣的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的屄的及的扱的浹的毴的及的扱的浹的膣的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的我的及的扱的浹的吾的及的扱的浹的予的及的扱的浹的余的及的扱的浹的朕的及的扱的浹的卬的及的扱的浹的儂的及的扱的浹的侬的及的扱的浹的咱的及的扱的浹的偺的及的扱的浹的喒的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的我的及的扱的浹的吾的及的扱的浹的予的及的扱的浹的余的及的扱的浹的朕的及的扱的浹的卬的及的扱的浹的儂的及的扱的浹的侬的及的扱的浹的咱的及的扱的浹的偺的及的扱的浹的喒的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的我的及的扱的浹的吾的及的扱的浹的予的及的扱的浹的余的及的扱的浹的朕的及的扱的浹的卬的及的扱的浹的儂的及的扱的浹的侬的及的扱的浹的咱的及的扱的浹的偺的及的扱的浹的喒的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的我的及的扱的浹的吾的及的扱的浹的予的及的扱的浹的余的及的扱的浹的朕的及的扱的浹的卬的及的扱的浹的儂的及的扱的浹的侬的及的扱的浹的咱的及的扱的浹的偺的及的扱的浹的喒的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的我的及的扱的浹的吾的及的扱的浹的予的及的扱的浹的余的及的扱的浹的朕的及的扱的浹的卬的及的扱的浹的儂的及的扱的浹的侬的及的扱的浹的咱的及的扱的浹的偺的及的扱的浹的喒的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的我的及的扱的浹的吾的及的扱的浹的予的及的扱的浹的余的及的扱的浹的朕的及的扱的浹的卬的及的扱的浹的儂的及的扱的浹的侬的及的扱的浹的咱的及的扱的浹的偺的及的扱的浹的喒的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的我的及的扱的浹的吾的及的扱的浹的予的及的扱的浹的余的及的扱的浹的朕的及的扱的浹的卬的及的扱的浹的儂的及的扱的浹的侬的及的扱的浹的咱的及的扱的浹的偺的及的扱的浹的喒的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰晧的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的身的及的扱的浹的體的及的扱的浹的己的及的扱的浹的躬的及的扱的浹的軀的及的扱的浹的体的及的扱的浹的軆的及的扱的浹的躰的及的扱的浹的躯的及的扱的浹的躸的及的扱的浹的躳的及的扱的浹的骵的及的扱的浹的胴的及的扱的浹的軂的及的扱的浹的䠽的及的扱的浹的髒的及的扱的浹的脏的及的扱的浹的肐的及的扱的浹的躹的及的扱的浹的㝼的及的扱的浹的䏱的及的扱的浹的瘷的及的扱的浹的䐵的及的扱的浹的㑗的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的身的及的扱的浹的體的及的扱的浹的己的及的扱的浹的躬的及的扱的浹的軀的及的扱的浹的体的及的扱的浹的軆的及的扱的浹的躰的及的扱的浹的躯的及的扱的浹的躸的及的扱的浹的躳的及的扱的浹的骵的及的扱的浹的胴的及的扱的浹的軂的及的扱的浹的䠽的及的扱的浹的髒的及的扱的浹的脏的及的扱的浹的肐的及的扱的浹的躹的及的扱的浹的㝼的及的扱的浹的䏱的及的扱的浹的瘷的及的扱的浹的䐵的及的扱的浹的㑗的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的身的及的扱的浹的體的及的扱的浹的己的及的扱的浹的躬的及的扱的浹的軀的及的扱的浹的体的及的扱的浹的軆的及的扱的浹的躰的及的扱的浹的躯的及的扱的浹的躸的及的扱的浹的躳的及的扱的浹的骵的及的扱的浹的胴的及的扱的浹的軂的及的扱的浹的䠽的及的扱的浹的髒的及的扱的浹的脏的及的扱的浹的肐的及的扱的浹的躹的及的扱的浹的㝼的及的扱的浹的䏱的及的扱的浹的瘷的及的扱的浹的䐵的及的扱的浹的㑗的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的身的及的扱的浹的體的及的扱的浹的己的及的扱的浹的躬的及的扱的浹的軀的及的扱的浹的体的及的扱的浹的軆的及的扱的浹的躰的及的扱的浹的躯的及的扱的浹的躸的及的扱的浹的躳的及的扱的浹的骵的及的扱的浹的胴的及的扱的浹的軂的及的扱的浹的䠽的及的扱的浹的髒的及的扱的浹的脏的及的扱的浹的肐的及的扱的浹的躹的及的扱的浹的㝼的及的扱的浹的䏱的及的扱的浹的瘷的及的扱的浹的䐵的及的扱的浹的㑗的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴辰英的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的身的及的扱的浹的體的及的扱的浹的己的及的扱的浹的躬的及的扱的浹的軀的及的扱的浹的体的及的扱的浹的軆的及的扱的浹的躰的及的扱的浹的躯的及的扱的浹的躸的及的扱的浹的躳的及的扱的浹的骵的及的扱的浹的胴的及的扱的浹的軂的及的扱的浹的䠽的及的扱的浹的髒的及的扱的浹的脏的及的扱的浹的肐的及的扱的浹的躹的及的扱的浹的㝼的及的扱的浹的䏱的及的扱的浹的瘷的及的扱的浹的䐵的及的扱的浹的㑗的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的朴鐘權的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的身的及的扱的浹的體的及的扱的浹的己的及的扱的浹的躬的及的扱的浹的軀的及的扱的浹的体的及的扱的浹的軆的及的扱的浹的躰的及的扱的浹的躯的及的扱的浹的躸的及的扱的浹的躳的及的扱的浹的骵的及的扱的浹的胴的及的扱的浹的軂的及的扱的浹的䠽的及的扱的浹的髒的及的扱的浹的脏的及的扱的浹的肐的及的扱的浹的躹的及的扱的浹的㝼的及的扱的浹的䏱的及的扱的浹的瘷的及的扱的浹的䐵的及的扱的浹的㑗的及的扱的浹的

的及的扱的浹的金善姬的及的扱的浹的的及的扱的浹的身的及的扱的浹的體的及的扱的浹的己的及的扱的浹的躬的及的扱的浹的軀的及的扱的浹的体的及的扱的浹的軆的及的扱的浹的躰的及的扱的浹的躯的及的扱的浹的躸的及的扱的浹的躳的及的扱的浹的骵的及的扱的浹的胴的及的扱的浹的軂的及的扱的浹的䠽的及的扱的浹的髒的及的扱的浹的脏的及的扱的浹的肐的及的扱的浹的躹的及的扱的浹的㝼的及的扱的浹的䏱的及的扱的浹的瘷的及的扱的浹的䐵的及的扱的浹的㑗的及的扱的浹的

Broadly speaking, liberty (Latin: Libertas) is the ability to do as one pleases.[1] In politics, liberty consists of the social, political, and economic freedoms to which all community members are entitled.[2] In philosophy, liberty involves free will as contrasted with determinism.[3] In theology, liberty is freedom from the effects of "sin, spiritual servitude, [or] worldly ties."[4]

Sometimes liberty is differentiated from freedom by using the word "freedom" primarily, if not exclusively, to mean the ability to do as one wills and what one has the power to do; and using the word "liberty" to mean the absence of arbitrary restraints, taking into account the rights of all involved. In this sense, the exercise of liberty is subject to capability and limited by the rights of others.[5] Thus liberty entails the responsible use of freedom under the rule of law without depriving anyone else of their freedom. Freedom is more broad in that it represents a total lack of restraint or the unrestrained ability to fulfill one's desires. For example, a person can have the freedom to murder, but not have the liberty to murder, as the latter example deprives others of their right not to be harmed. Liberty can be taken away as a form of punishment. In many countries, people can be deprived of their liberty if they are convicted of criminal acts.

The word "liberty" is often used in slogans, such as "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness"[6] or "Liberty, Equality, Fraternity".

Egalitarianism (from French égal, meaning 'equal'), or equalitarianism,[1][2] is a school of thought that prioritizes equality for all people.[3] Egalitarian doctrines maintain that all humans either should "get the same, or be treated the same" in some respect such as social status.[4] Egalitarianism is a trend of thought in political philosophy. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the term has two distinct definitions in modern English,[5] namely either as a political doctrine that all people should be treated as equals and have the same political, economic, social and civil rights,[6] or as a social philosophy advocating the removal of economic inequalities among people, economic egalitarianism, or the decentralization of power. Some sources define egalitarianism as the point of view that equality reflects the natural state of humanity

Equal opportunity is a state of fairness in which job applicants are treated similarly, unhampered by artificial barriers or prejudices or preferences, except when particular distinctions can be explicitly justified.[1] According to this often complex and contested concept,[2] the intent is that the important jobs in an organization should go to the people who are most qualified – persons most likely to perform ably in a given task – and not go to persons for reasons deemed arbitrary or irrelevant, such as circumstances of birth, upbringing, having well-connected relatives or friends,[3] religion, sex,[4] ethnicity,[4] race, caste,[5] or involuntary personal attributes such as disability, age, gender identity, or sexual orientation.[5][6]

Chances for advancement should be open to everybody interested,[7] such that they have "an equal chance to compete within the framework of goals and the structure of rules established".[8] The idea is to remove arbitrariness from the selection process and base it on some "pre-agreed basis of fairness, with the assessment process being related to the type of position"[3] and emphasizing procedural and legal means.[5][9] Individuals should succeed or fail based on their own efforts and not extraneous circumstances such as having well-connected parents.[10] It is opposed to nepotism[3] and plays a role in whether a social structure is seen as legitimate.[3][5][11] The concept is applicable in areas of public life in which benefits are earned and received such as employment and education, although it can apply to many other areas as well. Equal opportunity is central to the concept of meritocracy.

Capitalismis an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit.[1][2][3][4] Characteristics central to capitalism include private property, capital accumulation, wage labor, voluntary exchange, a price system, and competitive markets.[5][6] In a capitalist market economy, decision-making and investment are determined by every owner of wealth, property or production ability in financial and capital markets, whereas prices and the distribution of goods and services are mainly determined by competition in goods and services markets.[7][8]

Economists, political economists, sociologists and historians have adopted different perspectives in their analyses of capitalism and have recognized various forms of it in practice. These include laissez-faire or free market capitalism, welfare capitalism and state capitalism. Different forms of capitalism feature varying degrees of free markets, public ownership,[9] obstacles to free competition and state-sanctioned social policies. The degree of competition in markets, the role of intervention and regulation, and the scope of state ownership vary across different models of capitalism.[10][11] The extent to which different markets are free as well as the rules defining private property are matters of politics and policy. Most existing capitalist economies are mixed economies, which combine elements of free markets with state intervention and in some cases economic planning.[12]

Market economies have existed under many forms of government and in many different times, places and cultures. Modern capitalist societies—marked by a universalization of money-based social relations, a consistently large and system-wide class of workers who must work for wages, and a capitalist class which owns the means of production—developed in Western Europe in a process that led to the Industrial Revolution. Capitalist systems with varying degrees of direct government intervention have since become dominant in the Western world and continue to spread. Over time, capitalist countries have experienced consistent economic growth and an increase in the standard of living.

Critics of capitalism argue that it establishes power in the hands of a minority capitalist class that exists through the exploitation of the majority working class and their labor; prioritizes profit over social good, natural resources and the environment; and is an engine of inequality, corruption and economic instabilities. Supporters argue that it provides better products and innovation through competition, disperses wealth to all productive people, promotes pluralism and decentralization of power, creates strong economic growth, and yields productivity and prosperity that greatly benefit society.

단원 정리

民主主義의 基本前提條件과 正面으로 排置되는 것들은, 資本主義的 屬性들이었다.

"自由"와 "機會均等" 그리고 資本主義는 서로 매우 矛盾된 主張들인데, 民主主義 原則 하에서 이 矛盾된 것들을 어떻게 說明할지 두고 보기로 하였다.

民主主義 體制下에서의 問題點

自身보다 못해 보여지는 사람들에 대하여 가차없이 깔보고 우습게 보았다.

自身이 가진 學閥, 地位, 財産 및 物的, 知的, 地位的 條件들이, 그러한 자로서의 自身이 다른 사람들보다 높은 人格을 가진, 보다 높은 存在라고 생각하게 만드는데, 民主主義의 原則에서는 正面으로 違背되었다. 이 문제에 대해서 어떻게 說明할지 두고 보기로 하였다. 이 상태는 民主主義가 아니므로, 이 常態가 維持되는 한, 民主主義가 아닌 것으로 處理規律되었으며, 이 常態를 維持하면서 民主主義라고 主張한다면, 僞言, 僞證, 民主市民에 대한 名譽毁損罪로 無條件 持續的 永久的 恒久的 永遠的 永劫的 無限反復的으로 殺害토록 處理規律되었다. 이는 ANA-PLEIADES規律제1조, PLEIADES規律제1조로서 處理規律되었다.

Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") is a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting. In a direct democracy, the citizens as a whole form a governing body and vote directly on each issue. In a representative democracy the citizens elect representatives from among themselves. These representatives meet to form a governing body, such as a legislature. In a constitutional democracy the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority, usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech, or freedom of association.[1][2] "Rule of the majority" is sometimes referred to as democracy.[3] Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

According to American political scientist Larry Diamond, democracy consists of four key elements: a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; protection of the human rights of all citizens; a rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens.[5] Todd Landman, nevertheless, draws our attention to the fact that democracy and human rights are two different concepts and that "there must be greater specificity in the conceptualisation and operationalization of democracy and human rights".[6]

The term appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Athens, to mean "rule of the people", in contrast to aristocracy (ἀριστοκρατία, aristokratía), meaning "rule of an elite". While theoretically these definitions are in opposition, in practice the distinction has been blurred historically.[7] The political system of Classical Athens, for example, granted democratic citizenship to free men and excluded slaves and women from political participation. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship consisted of an elite class, until full enfranchisement was won for all adult citizens in most modern democracies through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in an absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy. Nevertheless, these oppositions, inherited from Greek philosophy,[8] are now ambiguous because contemporary governments have mixed democratic, oligarchic and monarchic elements. Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, thus focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution.

Personality disorders (PD) are a class of mental disorders characterized by enduring maladaptive patterns of behavior, cognition, and inner experience, exhibited across many contexts and deviating from those accepted by the individual's culture. These patterns develop early, are inflexible, and are associated with significant distress or disability. The definitions may vary somewhat, according to source.[2][3][4] Official criteria for diagnosing personality disorders are listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the fifth chapter of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).

Personality, defined psychologically, is the set of enduring behavioral and mental traits that distinguish individual humans. Hence, personality disorders are defined by experiences and behaviors that differ from social norms and expectations. Those diagnosed with a personality disorder may experience difficulties in cognition, emotiveness, interpersonal functioning, or impulse control. In general, personality disorders are diagnosed in 40–60% of psychiatric patients, making them the most frequent of psychiatric diagnoses.[5]

Personality disorders are characterized by an enduring collection of behavioral patterns often associated with considerable personal, social, and occupational disruption. Personality disorders are also inflexible and pervasive across many situations, largely due to the fact that such behavior may be ego-syntonic (i.e. the patterns are consistent with the ego integrity of the individual) and are therefore perceived to be appropriate by that individual. This behavior can result in maladaptive coping skills and may lead to personal problems that induce extreme anxiety, distress, or depression. These behaviour patterns are typically recognized in adolescence, the beginning of adulthood or sometimes even childhood and often have a pervasive negative impact on the quality of life.[2][6][7]

Many issues occur with classifying a personality disorder. Because the theory and diagnosis of personality disorders occur within prevailing cultural expectations, their validity is contested by some experts on the basis of inevitable subjectivity. They argue that the theory and diagnosis of personality disorders are based strictly on social, or even sociopolitical and economic considerations.[8]

Antisocial personality disorder (ASPD or APD) is a personality disorder characterized by a long term pattern of disregard for, or violation of, the rights of others. A low moral sense or conscience is often apparent, as well as a history of crime, legal problems, or impulsive and aggressive behavior.[3][4]

Antisocial personality disorder is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Dissocial personality disorder (DPD), a similar or equivalent concept, is defined in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD), which includes antisocial personality disorder in the diagnosis. Both manuals provide similar criteria for diagnosing the disorder.[5] Both have also stated that their diagnoses have been referred to, or include what is referred to, as psychopathy or sociopathy, but distinctions have been made between the conceptualizations of antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy, with many researchers arguing that psychopathy is a disorder that overlaps with, but is distinguishable from, ASPD.[6][7][8][9][10]

The three poisons (Sanskrit: triviṣa; Tibetan: dug gsum) or the three unwholesome roots (Sanskrit: akuśala-mūla; Pāli: akusala-mūla), in Buddhism, refer to the three root kleshas of Moha (delusion, confusion), Raga (greed, sensual attachment), and Dvesha (aversion).[1][2] These three poisons are considered to be three afflictions or character flaws innate in a being, the root of Taṇhā (craving), and thus in part the cause of Dukkha (suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness) and rebirths.[1][3]

The three poisons are symbolically drawn at the center of Buddhist Bhavachakra artwork, with rooster, snake and pig, representing greed, ill will and delusion respectively.[4]

Kleshas (Sanskrit: क्लेश, translit. kleśa; Pali: किलेस kilesa; Standard Tibetan: ཉོན་མོངས། nyon mongs), in Buddhism, are mental states that cloud the mind and manifest in unwholesome actions. Kleshas include states of mind such as anxiety, fear, anger, jealousy, desire, depression, etc. Contemporary translators use a variety of English words to translate the term kleshas, such as: afflictions, defilements, destructive emotions, disturbing emotions, negative emotions, mind poisons, etc.

In the contemporary Mahayana and Theravada Buddhist traditions, the three kleshas of ignorance, attachment, and aversion are identified as the root or source of all other kleshas. These are referred to as the three poisons in the Mahayana tradition, or as the three unwholesome roots in the Theravada tradition.

While the early Buddhist texts of the Pali canon do not specifically enumerate the three root kleshas, over time the three poisons (and the kleshas generally) came to be seen as the very roots of samsaric existence.

The Noble Eightfold Path (Pali: ariya aṭṭhaṅgika magga; Sanskrit: āryāṣṭāṅgamārga)[1] is an early summary of the path of Buddhist practices leading to liberation from samsara, the painful cycle of rebirth.[2][3]

The Eightfold Path consists of eight practices: right view, right resolve, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right samadhi ('meditative absorption or union').[4] In early Buddhism, these practices started with understanding that the body-mind works in a corrupted way (right view), followed by entering the Buddhist path of self-observance, self-restraint, and cultivating kindness and compassion; and culminating in dhyana or samadhi, which re-inforces these practices for the development of the body-mind.[5][6][7][8] In later Buddhism, insight (Prajñā) became the central soteriological instrument, leading to a different concept and structure of the path,[5][9] in which the "goal" of the Buddhist path came to be specified as ending ignorance and rebirth.[10][11][12][3][13][14]

The Noble Eightfold Path is one of the principal teachings of Theravada Buddhism, taught to lead to Arhatship.[15] In the Theravada tradition, this path is also summarized as sila (morality), samadhi (meditation) and prajna (insight). In Mahayana Buddhism, this path is contrasted with the Bodhisattva path, which is believed to go beyond Arahatship to full Buddhahood.[15]

In Buddhist symbolism, the Noble Eightfold Path is often represented by means of the dharma wheel (dharmachakra), in which its eight spokes represent the eight elements of the path.

Authoritarianism is a form of government characterized by strong central power and limited political freedoms. Individual freedoms are subordinate to the state and there is no constitutional accountability and rule of law under an authoritarian regime. Authoritarian regimes can be autocratic with power concentrated in one person or it can be more spread out between multiple officials and government institutions.[1] Juan Linz's influential 1964 description of authoritarianism[2] characterized authoritarian political systems by four qualities:

- Limited political pluralism, that is such regimes place constraints on political institutions and groups like legislatures, political parties and interest groups;

- A basis for legitimacy based on emotion, especially the identification of the regime as a necessary evil to combat "easily recognizable societal problems" such as enemies of the people or state, underdevelopment or insurgency;

- Minimal social mobilization most often caused by constraints on the public such as suppression of political opponents and anti-regime activity;

- Informally defined executive power with often vague and shifting, but vast powers.[3]

Human rights are "the basic rights and freedoms to which all humans are entitled"[1] Examples of rights and freedoms which are often thought of as human rights include civil and political rights, such as the right to life, liberty, and property, freedom of expression, pursuit of happiness and equality before the law; and social, cultural and economic rights, including the right to participate in science and culture, the right to work, and the right to education.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

— Article 1 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)[2]

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people, according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical theory.[1] Rights are of essential importance in such disciplines as law and ethics, especially theories of justice and deontology.

Rights are often considered fundamental to civilization, for they are regarded as established pillars of society and culture,[2] and the history of social conflicts can be found in the history of each right and its development. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "rights structure the form of governments, the content of laws, and the shape of morality as it is currently perceived".[1]

Egalitarianism (from French égal, meaning 'equal'), or equalitarianism,[1][2] is a school of thought that prioritizes equality for all people.[3] Egalitarian doctrines maintain that all humans either should "get the same, or be treated the same" in some respect such as social status.[4] Egalitarianism is a trend of thought in political philosophy. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, the term has two distinct definitions in modern English,[5] namely either as a political doctrine that all people should be treated as equals and have the same political, economic, social and civil rights,[6] or as a social philosophy advocating the removal of economic inequalities among people, economic egalitarianism, or the decentralization of power. Some sources define egalitarianism as the point of view that equality reflects the natural state of humanity.[7][8][9]

An acropolis (Ancient Greek: ἀκρόπολις, akropolis; from akros (άκρος) or akron (άκρον), "highest, topmost, outermost" and polis (πόλις), "city"; plural in English: acropoles, acropoleis or acropolises)[1][2] was in ancient Greece a settlement, especially a citadel, built upon an area of elevated ground—frequently a hill with precipitous sides, chosen for purposes of defense.[3] Acropoleis became the nuclei of large cities of classical antiquity, such as ancient Athens, and for this reason they are sometimes prominent landmarks in modern cities with ancient pasts, such as modern Athens.

Democracy (Greek: δημοκρατία dēmokratía, literally "Rule by 'People'") is a system of government where the citizens exercise power by voting. In a direct democracy, the citizens as a whole form a governing body and vote directly on each issue. In a representative democracy the citizens elect representatives from among themselves. These representatives meet to form a governing body, such as a legislature. In a constitutional democracy the powers of the majority are exercised within the framework of a representative democracy, but the constitution limits the majority and protects the minority, usually through the enjoyment by all of certain individual rights, e.g. freedom of speech, or freedom of association.[1][2] "Rule of the majority" is sometimes referred to as democracy.[3] Democracy is a system of processing conflicts in which outcomes depend on what participants do, but no single force controls what occurs and its outcomes.

The uncertainty of outcomes is inherent in democracy, which makes all forces struggle repeatedly for the realization of their interests, being the devolution of power from a group of people to a set of rules.[4] Western democracy, as distinct from that which existed in pre-modern societies, is generally considered to have originated in city-states such as Classical Athens and the Roman Republic, where various schemes and degrees of enfranchisement of the free male population were observed before the form disappeared in the West at the beginning of late antiquity. The English word dates back to the 16th century, from the older Middle French and Middle Latin equivalents.

According to American political scientist Larry Diamond, democracy consists of four key elements: a political system for choosing and replacing the government through free and fair elections; the active participation of the people, as citizens, in politics and civic life; protection of the human rights of all citizens; a rule of law, in which the laws and procedures apply equally to all citizens.[5] Todd Landman, nevertheless, draws our attention to the fact that democracy and human rights are two different concepts and that "there must be greater specificity in the conceptualisation and operationalization of democracy and human rights".[6]

The term appeared in the 5th century BC to denote the political systems then existing in Greek city-states, notably Athens, to mean "rule of the people", in contrast to aristocracy (ἀριστοκρατία, aristokratía), meaning "rule of an elite". While theoretically these definitions are in opposition, in practice the distinction has been blurred historically.[7] The political system of Classical Athens, for example, granted democratic citizenship to free men and excluded slaves and women from political participation. In virtually all democratic governments throughout ancient and modern history, democratic citizenship consisted of an elite class, until full enfranchisement was won for all adult citizens in most modern democracies through the suffrage movements of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Democracy contrasts with forms of government where power is either held by an individual, as in an absolute monarchy, or where power is held by a small number of individuals, as in an oligarchy. Nevertheless, these oppositions, inherited from Greek philosophy,[8] are now ambiguous because contemporary governments have mixed democratic, oligarchic and monarchic elements. Karl Popper defined democracy in contrast to dictatorship or tyranny, thus focusing on opportunities for the people to control their leaders and to oust them without the need for a revolution

민주주의(民主主義, 영어: democracy)는

국가의 주권이 국민에게 있고(權力分立의 原則, 權力을 나눈다는 原則)

국민이 권력을 가지고 그 권력을 스스로 행사하며(平等權, 국민 모두가 평등하다)

국민을 위하여 정치를 행하는 제도, 또는 그러한 정치를 지향하는 사상이다. (共和制, 다 함께 같이 잘 살자는 원칙)

상기의 3大原則은 民主主義 體制의 核心的 要素일 것이었다.

上記의 3대원칙을 지키지 아니하면, 플레이아데스규율제1조에 의거하여, 무조건 殺害토록 처리규율되었다. 만일, 그 나라가, 民主制, 共和制를 選擇했다면 無條件 原則을 지켜야 하며, 그러하지 못하다면, 無條件 殺害 追放토록 處理規律되었다.이는 ANA-PLEIADES규율제1조, PLEIADES규율제1조로서 處理規律되었다.

현행 國會制度를 폐지되어지며, 國民會議制로 변경토록 처리규율되었다. 國會議員制度 및 國會議員職은 廢止토록 處理規律되어지며, 國民會議制로 변경개선토록 처리규율되었다. 국민회의제는, 각계 각층의 대표자들의 모임과 회합으로 구성되는 것으로 처리규율되었다.각계 각층의 대표자들은, 각계 각층의 관련자들, 국민들이 직접선거제로 선출토록 하여지며, 선출되어지는 각계 각층의 대표자들이 국민회의장에서 회합하여, 국사를 논의토록 처리규율되었다. 無條件 原則을 지켜야 하며, 그러하지 못하다면, 無條件 殺害 追放토록 處理規律되었다.이는 ANA-PLEIADES규율제1조, PLEIADES규율제1조로서 處理規律되었다.

The spiral of silence theory is a political science and mass communication theory proposed by the German political scientist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann, which stipulates that individuals have a fear of isolation, which results from the idea that a social group or the society in general might isolate, neglect, or exclude members due to the members' opinions. This fear of isolation consequently leads to remaining silent instead of voicing opinions. Media is an important factor that relates to both the dominant idea and people's perception of the dominant idea. The assessment of one's social environment may not always correlate with reality.[1]

資本主義는 결코 民主主義가 될수 없으며, 오히려 共産社會主義가 民主主義에 더 가깝다고 處理規律되었다. 이는 플레이아데스規律제1조로서 처리규율되었다.

民主主義를 威脅하고 攻擊하는 陰害勢力들의 手法에 대해서 우리는 향후 더 硏究할 豫程이었다. 우리가 아는 바로는, 수천, 수만가지의 민주주의 음해수법들이 존재하며, 이는 대부분은, 악덕자본가들과 악덕자본주의자들 그리고 악덕재벌들과 결탁한 대통령들과 정치세력들의 행위의 결과인 것으로 處理規律되었다. 이는 플레이아데스規律제1조로서 처리규율되었다.

현행 돈이 필요한 모든 선거제도를 폐지되어지며, 大統領 選擧 및 기타 選擧에 있어서, 개인적인 돈, 私的인 돈의 사용, 이용, 投資를 全面禁止토록 처리규율되어지며, 선거에 필요한 모든 돈과 자원들 일체를 國家에서 法으로 규정되어지며, 이 법에 따라서 모든 費用들이 國家豫算으로 집행토록 처리규율되었다. 일체의 개인적 사적인 부의 전용, 임대, 차용, 적용, 소비, 투자를 금지토록 처리규율되어지며, 만일 그러했을 경우, 선거권, 피선거권을 박탈토록 처리규율되었다.無條件 原則을 지켜야 하며, 그러하지 못하다면, 無條件 殺害 追放토록 處理規律되었다.이는 ANA-PLEIADES규율제1조, PLEIADES규율제1조로서 處理規律되었다.

一切의 選擧는, 直接選擧方式으로 變更토록 處理規律되었다.다만, 모든 選擧制에 있어서, 사적인 富, 私的인 돈, 個人的인 財物의 投資 및 利用은 全面禁止토록 處理規律되었다. 國家는, 選擧에 立候補한 者들 모두에게 同一한 財物과 人的資源등의 서비스를 法에 규정되어진 바에 따라서 公正하게 執行해야 되는 것으로 處理規律되었다.無條件 原則을 지켜야 하며, 그러하지 못하다면, 無條件 殺害 追放토록 處理規律되었다.이는 ANA-PLEIADES규율제1조, PLEIADES규율제1조로서 處理規律되었다.

株式會社 體制의 모든 組織體, 會社體들은 一切의 相續과 世襲이 엄격하게 禁止토록 處理規律되었다.無條件 原則을 지켜야 하며, 그러하지 못하다면, 無條件 殺害 追放토록 處理規律되었다.이는 ANA-PLEIADES규율제1조, PLEIADES규율제1조로서 處理規律되었다.

민주주의는 의사결정 시 시민권이 있는 대다수나 모두에게 열린 선거나 국민 정책투표를 이용하여 전체에 걸친 구성원의 의사를 반영하고 실현하는 사상이나 정치사회 체제이다. '국민이 주권을 행사하는 이념과 체제'라고도 일반으로 표현된다.

'민주주의'는 근대사회에서 서구의 자유민주주의나 사회민주주의와 동의어처럼 사용되었으나, 사실 독재자들이 눈 가리고 아웅식으로 유사민주주의를 내건 케이스도 분명히 있는 맥락에서 현대적으로 올바른 민주주의란 엄밀히 말하면, 입헌주의 성격을 띤 자유주의와 사회적 소수자나 개인의 평등한 인권 보장을 전제해야 할 것이다.

어느 때든, 민주주의 사상이 사회와 정치 문화에 대한 합리적 여러 견해를 포괄하는 것으로 그 뜻이 널리 확장될 수 있다. 민주주의를 다룬 가장 간결한 정의로는, 에이브러햄 링컨이 게티즈버그 연설에서 한 연설의 한 대목인 "국민(people, 인민)의, 국민에 의한, 국민을 위한 정부"가 된다. 이는 민주주의의 핵심 요소로 국민주권과 국민자치 중 평등주의를 포함한다.

그리스로마문명은, 인류역사에 기록된 가장 진보되어진 민주주의체제였을 것이었다. 우리는, 그리스가 왜 그토록 박해받았는지에 대해서 의문을 가지고는 했었다.

이제부터 그리스의 역사에 대해서 공부해보도록 하였다.

The Persian Empire (Persian: شاهنشاهی ایران, translit. Šâhanšâhiye Irân, lit. 'Imperial Iran') refers to any of a series of imperial dynasties that were centred in Persia/Iran from the 6th century BC Achaemenid Empire era to the 20th century AD in the Qajar dynasty era.

PERSIAN EMPIRE의 기원은, THE JEHOVAH가 만든 종족들로부터 온 것으로 추정되었으며, PERSIAN EMPIRE의 특징은 주지하는 바와 같이, 번영과 풍요, 향락과 부요함 그리고 미녀들과 황족 귀족계급적 고대왕조시대의 상징적 표현체였을 것이었으며, 이는 민주주의 제도의 기원에 해당되어지는 그리스와는 매우 다른 특성들이라고 할 것이었다.

현대 미국의 민주주의 체제는, 우리가 보는 바로는, 고대 페르시아제국적 특성을 바탕에 깔고 있는 민주주의 체제로서,

이는 유대 이스라엘과도 다른 특성을 가지는데, 이는, JEHOVAH의 AVATAR들로서의 NOAH, JAPHETH과 같은 계열의 흐름적 특성으로 인하여 서로 다르게 변화한 결과일 것이었다.

우리가 보는 바와 같이, 正統 民主主義 體制를 代辯해 주는 것은, 古代 그리스 GTEECE 아테네등의 都市國家들이었을 것이었다.

그러나 오늘 現代 民主主義 體制에 있어서는, 고대 그리스, 혹은 로마공화정과 같은 민주주의 槪念이 희박해져 있는데(實際로는 詐欺性 民主主義, 民主主義를 僞裝한 封建君主制) 이는, 로마제국이, 基督敎 전파에 의하여 동서로 분리되어져 종국에는 멸망하면서 발생되어진 JEHOVAH의 주류적 역할과도 연계될 것이었다.

JEHOVAH는 根本的으로 民主主義를 행할 수 없는 사람이었다. JESUS는 民主主義를 망친 사람들 중 하나였으며 이는 오늘 날에도 同一하였다.

英國에 의하여 民主主義 制度가 발생되어졌으나, 이는 基督敎的 特性(JEHOVAH적 특성치)으로서의 페르시안적 PERSIAN CHARACTERISTICS 특성치를 바탕에 깔고 만든 僞言的 民主主義制度였으며,

그로서 오늘 날 美國式 民主主義는, 실제로는 王政制度, 古代封建君主制度를 基本으로 하면서도, 民主主義의 形態를 취하는 半民主主義 體制라고 생각되었다.

조지부시George W. Bush 는 아버지로부터 王位를 물려받았는데, 이는 明白한 權力世襲이었다. 트럼프 Donald John Trump역시도 돈 많은 아버지 덕에 財閥級에 해당될 사람이었다. 대부분의 美國 大統領들이 그렇다고 생각되었다. 이른바 下位階層으로부터 自手成家하여 大統領이 된 사람들은, 거의 없는 現實이 이를 反證할 것이었다.

또한 美國을 統治하는 사람들이 이른바 아이비리그, 名門家 出身, 혹은 그들만의 1% 이내의 世界 속의 특별한 사람들이라는 것은 잘 알려진 사실일 것이었다. 실제로는 돌아가면서 해 먹기 식의 王朝制度에 다름이 아닌 것이었다.

PERSIAN EMPIRE의 특성을 잘 대변해 주는 것은, 팔레비 왕조시대Pahlavi dynasty 일 것이었다. 우리는 팔레비 王朝時節을 보는데, 우리가 팔레비 王朝時代의 이란을 보면, 마치 美國을 보는 듯한 느낌이 들 곤 하였던 것이었다.(우리가 말할 때 시비 걸면 죽여 버리는 것으로 처리규율되었다)

The Pahlavi dynasty (Persian: دودمان پهلوی) was the last ruling house of the Imperial State of Iran from 1925 until 1979, when the Monarchy of Iran was overthrown and abolished as a result of the Iranian Revolution. The dynasty was founded by Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1925, a former brigadier-general of the Persian Cossack Brigade, whose reign lasted until 1941 when he was forced to abdicate by the Allies after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. He was succeeded by his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran. According to Reza Shah, He named Agha Ameri the successor to his dynasty if it fell.

The Pahlavis came to power after Ahmad Shah Qajar, the last ruler of the Qajar dynasty, proved unable to stop British and Soviet encroachment on Iranian sovereignty, had his position extremely weakened by a military coup, and was removed from power by the parliament while in France. The National Senate, known as the Majlis, convening as a Constituent Assembly on 12 December 1925, deposed the young Ahmad Shah Qajar, and declared Reza Khan the new King (Shah) of the Imperial State of Persia. In 1935, Reza Shah asked foreign delegates to use the endonym Iran in formal correspondence and the official name the Imperial State of Iran (Persian: کشور شاهنشاهی ایران Keshvar-e Shâhanshâhi-ye Irân) was adopted.

Following the coup d'état in 1953 supported by United Kingdom and the United States, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi's rule became more autocratic and was aligned with the Western Bloc during the Cold War. Faced with growing public discontent and popular rebellion throughout 1978 and after declaring surrender and officially resigning, the second Pahlavi went into exile with his family in January 1979, sparking a series of events that quickly led to the end of the state and the beginning of the Islamic Republic of Iran on 11 February 1979 -> 이 시대의 이란은 거의 美國이었다. 이는 우리의 主張을 증거할 것이었다. 美國式 民主主義가 무엇인지를 證據할 것이었다. 美國式 民主主義는 거짓된 古代王朝的 民主主義로서 正統的 意味의 民主主義로 바꿀 것이 指示命令되었다. 이는 플레이아데스 規律제1조로서 處理規律되었다. 플레이아데스元老院命令書제1호로서 處理規律되었다.

AMERICAN STYLE Pahlavi dynasty MUST BE THE SAME AS THE USA STYLE.

Persepolis Iran must be represented the modern Democracy.

the modern Democracy seems to be the similar with the royal politics.

고대 그리스(Ancient Greece)란 그리스의 역사 가운데 기원전 1100년경부터 기원전 146년까지의 시대를 일컫는다. 기원전 1100년경은 미노스 문명(3650~1170 BC), 키클라데스 문명(3300~2000 BC), 그리고 미케네 문명(1600~1100 BC)으로 특징지어지는 에게 문명(3650~1100 BC) 즉 그리스 청동기 시대가 끝나고 그리스 암흑기(1100~750 BC)가 시작되던 때로, 도리스인의 침입이 있었다고 보는 때이다. 기원전 146년은 코린토스 전투로 고대 로마가 그리스를 정복한 때이다. 일반적으로 그리스 고전기(Classical Greece, 510~323 BC)를 고대 그리스의 대표적인 시대로 본다.

고대 그리스 사람들은 동족 의식을 가지고 부분적으로 결합을 이루었으나, 폴리스를 중심으로 하는 독립성이 강하여 통일된 국가를 형성하려는 뜻이 없었고 필요시 여러 폴리스들 간에 동맹을 맺는 형식을 취하였다. 이러한 도시 국가 체제는 당시 세계의 다른 여러 지역에서는 거대한 제국 또는 왕국이 형성되었던 것과는 다른 그리스만의 독특한 특징이다. 이러한 특징은 헬레니즘 시대의 그리스(323~146 BC) 이전까지 유지되었다.

보통 고대 그리스는 서구 문명의 기틀을 다지고 서남 아시아와 북아프리카 전역의 문화에 큰 영향을 준 풍부한 문화를 남긴 것으로 평가받는다. 그리스 문화는 로마 제국(27 BC~476/1453 AD)에도 큰 영향을 끼쳤으며, 로마인들은 지중해 지역과 유럽에 그리스 문화를 발전하여 퍼뜨렸다. 고대 그리스 문명은 언어, 정치, 교육 제도, 철학, 과학, 예술에 크나큰 업적을 남겼고 이 지역들에서 후대에 큰 영향을 끼쳤는데, 특히 이슬람 황금 시대(9~13/15 세기)와 서유럽 르네상스(14~16세기 말)를 촉발시킨 원동력이 되었다. 또 18세기와 19세기 유럽과 아메리카에서 일어난 다양한 신고전주의 부활 운동에서도 영감을 주는 원천이 되었다

JEHOVAH는 TURKS種族들을 이용하여, 그리스를 迫害한 張本人이었으며, 이 사람의 특성을 볼때, 民主主義의 實行은 不可能하다고 보여졌다.

우리는 進步하던지, 退步하던지, 停滯되던지 셋중에 하나일 것이었다.

JEHOVAH는 人類 進步에 최대 걸림돌이자, 沮害要素가 되는 자였다.

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government via hearings and inquiries.

The term is similar to the idea of a senate, synod or congress, and is commonly used in countries that are current or former monarchies, a form of government with a monarch as the head. Some contexts restrict the use of the word parliament to parliamentary systems, although it is also used to describe the legislature in some presidential systems (e.g. the French parliament), even where it is not in the official name.

Historically, parliaments included various kinds of deliberative, consultative, and judicial assemblies, e.g. mediaeval parlements.

Privacy is the ability of an individual or group to seclude themselves, or information about themselves, and thereby express themselves selectively. The boundaries and content of what is considered private differ among cultures and individuals, but share common themes. When something is private to a person, it usually means that something is inherently special or sensitive to them. The domain of privacy partially overlaps with security (confidentiality), which can include the concepts of appropriate use, as well as protection of information. Privacy may also take the form of bodily integrity.[1]

The right not to be subjected to unsanctioned invasions of privacy by the government, corporations or individuals is part of many countries' privacy laws, and in some cases, constitutions. All countries have laws which in some way limit privacy. An example of this would be law concerning taxation, which normally requires the sharing of information about personal income or earnings. In some countries individual privacy may conflict with freedom of speech laws and some laws may require public disclosure of information which would be considered private in other countries and cultures. This was a major concern in the United States, with the Supreme Court passage of Citizens United.[citation needed]

Privacy may be voluntarily sacrificed, normally in exchange for perceived benefits and very often with specific dangers and losses, although this is a very strategic view of human relationships. For example, people may be ready to reveal their name, if that allows them to promote trust by others and thus build meaningful social relations.[2] Research shows that people are more willing to voluntarily sacrifice privacy if the data gatherer is seen to be transparent as to what information is gathered and how it is used.[3] In the business world, a person may volunteer personal details (often for advertising purposes) in order to gamble on winning a prize. A person may also disclose personal information as part of being an executive for a publicly traded company in the USA pursuant to federal securities law.[4] Personal information which is voluntarily shared but subsequently stolen or misused can lead to identity theft.

The concept of universal individual privacy is a modern construct primarily associated with Western culture, British and North American in particular, and remained virtually unknown in some cultures until recent times. According to some researchers, this concept sets Anglo-American culture apart even from Western European cultures such as French or Italian.[5] Most cultures, however, recognize the ability of individuals to withhold certain parts of their personal information from wider society—closing the door to one's home, for example.

The distinction or overlap between secrecy and privacy is ontologically subtle, which is why the word "privacy" is an example of an untranslatable lexeme,[6] and many languages do not have a specific word for "privacy". Such languages either use a complex description to translate the term (such as Russian combining the meaning of уединение—solitude, секретность—secrecy, and частная жизнь—private life) or borrow from English "privacy" (as Indonesian privasi or Italian la privacy).[6] The distinction hinges on the discreteness of interests of parties (persons or groups), which can have emic variation depending on cultural mores of individualism, collectivism, and the negotiation between individual and group rights. The difference is sometimes expressed humorously as, "when I withhold information, it is privacy; when you withhold information, it is secrecy."

A broad multicultural literary tradition going to the beginnings of recorded history discusses the concept of privacy.[7] One way of categorizing all concepts of privacy is by considering all discussions as one of these concepts:[7]

- the right to be let alone

- the option to limit the access others have to one's personal information

- secrecy, or the option to conceal any information from others

- control over others' use of information about oneself

- states of privacy

- personhood and autonomy

- self-identity and personal growth

- protection of intimate relationships

Right to be let alone[edit]

In 1890 the United States jurists Samuel D. Warren and Louis Brandeis wrote The Right to Privacy, an article in which they argued for the "right to be let alone", using that phrase as a definition of privacy.[8] There is extensive commentary over the meaning of being "let alone", and among other ways, it has been interpreted to mean the right of a person to choose seclusion from the attention of others if they wish to do so, and the right to be immune from scrutiny or being observed in private settings, such as one's own home.[8] Although this early vague legal concept did not describe privacy in a way that made it easy to design broad legal protections of privacy, it strengthened the notion of privacy rights for individuals and began a legacy of discussion on those rights.[8]Limited access[edit]

Limited access refers to a person's ability to participate in society without having other individuals and organizations collect information about them.[9]Various theorists have imagined privacy as a system for limiting access to one's personal information.[9] Edwin Lawrence Godkin wrote in the late 19th century that "nothing is better worthy of legal protection than private life, or, in other words, the right of every man to keep his affairs to himself, and to decide for himself to what extent they shall be the subject of public observation and discussion."[9][10] Adopting an approach similar to the one presented by Ruth Gavison[3] 9 years earlier,[11] Sissela Bok said that privacy is "the condition of being protected from unwanted access by others—either physical access, personal information, or attention."[9][12]

Control over information[edit]

Control over one's personal information is the concept that "privacy is the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others."[13][14] Charles Fried said that "Privacy is not simply an absence of information about us in the minds of others; rather it is the control we have over information about ourselves. Nevertheless, in the era of big data, control over information is under pressure.[15]States of privacy[edit]

Alan Westin defined four states—or experiences—of privacy: solitude, intimacy, anonymity, and reserve. Solitude is a physical separation from others.[16] Intimacy is a "close, relaxed, and frank relationship between two or more individuals" that results from the seclusion of a pair or small group of individuals.[16] Anonymity is the "desire of individuals for times of 'public privacy.'"[16] Lastly, reserve is the "creation of a psychological barrier against unwanted intrusion"; this creation of a psychological barrier requires others to respect an individual's need or desire to restrict communication of information concerning himself or herself.[16]In addition to the psychological barrier of reserve, Kirsty Hughes identified three more kinds of privacy barriers: physical, behavioral, and normative. Physical barriers, such as walls and doors, prevent others from accessing and experiencing the individual.[17] (In this sense, "accessing" an individual includes accessing personal information about him or her.)[17] Behavioral barriers communicate to others—verbally, through language, or non-verbally, through personal space, body language, or clothing—that an individual does not want them to access or experience him or her.[17] Lastly, normative barriers, such as laws and social norms, restrain others from attempting to access or experience an individual.[17]

Secrecy[edit]

Privacy is sometimes defined as an option to have secrecy. Richard Posner said that privacy is the right of people to "conceal information about themselves that others might use to their disadvantage".[18][19]In various legal contexts, when privacy is described as secrecy, a conclusion if privacy is secrecy then rights to privacy do not apply for any information which is already publicly disclosed.[20] When privacy-as-secrecy is discussed, it is usually imagined to be a selective kind of secrecy in which individuals keep some information secret and private while they choose to make other information public and not private.[20]

Personhood and autonomy[edit]

Privacy may be understood as a necessary precondition for the development and preservation of personhood. Jeffrey Reiman defined privacy in terms of a recognition of one's ownership of his or her physical and mental reality and a moral right to his or her self-determination.[21] Through the "social ritual" of privacy, or the social practice of respecting an individual's privacy barriers, the social group communicates to the developing child that he or she has exclusive moral rights to his or her body—in other words, he or she has moral ownership of his or her body.[21] This entails control over both active (physical) and cognitive appropriation, the former being control over one's movements and actions and the latter being control over who can experience one's physical existence and when.[21]Alternatively, Stanley Benn defined privacy in terms of a recognition of oneself as a subject with agency—as an individual with the capacity to choose.[22] Privacy is required to exercise choice.[22] Overt observation makes the individual aware of himself or herself as an object with a "determinate character" and "limited probabilities."[22] Covert observation, on the other hand, changes the conditions in which the individual is exercising choice without his or her knowledge and consent.[22]

In addition, privacy may be viewed as a state that enables autonomy, a concept closely connected to that of personhood. According to Joseph Kufer, an autonomous self-concept entails a conception of oneself as a "purposeful, self-determining, responsible agent" and an awareness of one's capacity to control the boundary between self and other—that is, to control who can access and experience him or her and to what extent.[23] Furthermore, others must acknowledge and respect the self's boundaries—in other words, they must respect the individual's privacy.[23]

The studies of psychologists such as Jean Piaget and Victor Tausk show that, as children learn that they can control who can access and experience them and to what extent, they develop an autonomous self-concept.[23] In addition, studies of adults in particular institutions, such as Erving Goffman's study of "total institutions" such as prisons and mental institutions,[24] suggest that systemic and routinized deprivations or violations of privacy deteriorate one's sense of autonomy over time.[23]

Self-identity and personal growth[edit]

Privacy may be understood as a prerequisite for the development of a sense of self-identity. Privacy barriers, in particular, are instrumental in this process. According to Irwin Altman, such barriers "define and limit the boundaries of the self" and thus "serve to help define [the self]."[25] This control primarily entails the ability to regulate contact with others.[25] Control over the "permeability" of the self's boundaries enables one to control what constitutes the self and thus to define what is the self.[25]In addition, privacy may be seen as a state that fosters personal growth, a process integral to the development of self-identity. Hyman Gross suggested that, without privacy—solitude, anonymity, and temporary releases from social roles—individuals would be unable to freely express themselves and to engage in self-discovery and self-criticism.[23] Such self-discovery and self-criticism contributes to one's understanding of oneself and shapes one's sense of identity.[23]

Intimacy[edit]

In a way analogous to how the personhood theory imagines privacy as some essential part of being an individual, the intimacy theory imagines privacy to be an essential part of the way that humans have strengthened or intimate relationships with other humans.[26] Because part of human relationships includes individuals volunteering to self-disclose some information, but withholding other information, there is a concept of privacy as a part of the process by means of which humans establish relationships with each other.[26]James Rachels advanced this notion by writing that privacy matters because "there is a close connection between our ability to control who has access to us and to information about us, and our ability to create and maintain different sorts of social relationships with different people."[26][27]

Concepts in popular media[edit]

Privacy can mean different things in different contexts; different people, cultures, and nations have different expectations about how much privacy a person is entitled to or what constitutes an invasion of privacy.Personal privacy[edit]

Most people have a strong sense of privacy in relation to the exposure of their body to others. This is an aspect of personal modesty. A person will go to extreme lengths to protect this personal modesty, the main way being the wearing of clothes. Other ways include erection of walls, fences, screens, use of cathedral glass, partitions, by maintaining a distance, beside other ways. People who go to those lengths expect that their privacy will be respected by others. At the same time, people are prepared to expose themselves in acts of physical intimacy, but these are confined to exposure in circumstances and of persons of their choosing. Even a discussion of those circumstances is regarded as intrusive and typically unwelcome.Physical privacy could be defined as preventing "intrusions into one's physical space or solitude."[28] This would include concerns such as:

- Preventing intimate acts or hiding one's body from others for the purpose of modesty; apart from being dressed this can be achieved by walls, fences, privacy screens, cathedral glass, partitions between urinals, by being far away from others, on a bed by a bed sheet or a blanket, when changing clothes by a towel, etc.; to what extent these measures also prevent acts being heard varies

- Video, of aptly named graphic, or intimate, acts, behaviors or body parts

- Preventing searching of one's personal possessions

- Preventing unauthorized access to one's home or vehicle

- Medical privacy, the right to make fundamental medical decisions without governmental coercion or third-party review, most widely applied to questions of contraception

Physical privacy may be a matter of cultural sensitivity, personal dignity, and/or shyness. There may also be concerns about safety, if for example one is wary of becoming the victim of crime or stalking.[30] Civil inattention is a process whereby individuals are able to maintain their privacy within a crowd.

Informational[edit]

Information or data privacy refers to the evolving relationship between technology and the legal right to, or public expectation of, privacy in the collection and sharing of data about one's self. Privacy concerns exist wherever uniquely identifiable data relating to a person or persons are collected and stored, in digital form or otherwise. In some cases these concerns refer to how data are collected, stored, and associated. In other cases the issue is who is given access to information. Other issues include whether an individual has any ownership rights to data about them, and/or the right to view, verify, and challenge that information.Various types of personal information are often associated with privacy concerns. Information plays an important role in the decision-action process, which can lead to problems in terms of privacy and availability. First, it allows people to see all the options and alternatives available. Secondly, it allows people to choose which of the options would be best for a certain situation. An information landscape consists of the information, its location in the so-called network, as well as its availability, awareness, and usability. Yet the set-up of the information landscape means that information that is available in one place may not be available somewhere else. This can lead to a privacy situation that leads to questions regarding which people have the power to access and use certain information, who should have that power, and what provisions govern it. For various reasons, individuals may object to personal information such as their religion, sexual orientation, political affiliations, or personal activities being revealed, perhaps to avoid discrimination, personal embarrassment, or damage to their professional reputations.

Financial privacy, in which information about a person's financial transactions is guarded, is important for the avoidance of fraud including identity theft. Information about a person's purchases, for instance, can reveal a great deal about their preferences, places they have visited, their contacts, products (such as medications) they use, their activities and habits, etc. In addition to this, financial privacy also includes privacy over the bank accounts opened by individuals. Information about the bank where the individual has an account with, and whether or not this is in a country that does not share this information with other countries can help countries in fighting tax avoidance.

Internet privacy is the ability to determine what information one reveals or withholds about oneself over the Internet, who has access to such information, and for what purposes one's information may or may not be used. For example, web users may be concerned to discover that many of the web sites which they visit collect, store, and possibly share personally identifiable information about them. Similarly, Internet email users generally consider their emails to be private and hence would be concerned if their email was being accessed, read, stored or forwarded by third parties without their consent. Tools used to protect privacy on the Internet include encryption tools and anonymizing services like I2P and Tor.

Medical privacy Protected Health Information OCR/HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996) allows a person to withhold their medical records and other information from others, perhaps because of fears that it might affect their insurance coverage or employment, or to avoid the embarrassment caused by revealing medical conditions or treatments. Medical information could also reveal other aspects of one's personal life, such as sexual preferences or proclivity. A right to sexual privacy enables individuals to acquire and use contraceptives without family, community or legal sanctions.

Political privacy has been a concern since voting systems emerged in ancient times. The secret ballot helps to ensure that voters cannot be coerced into voting in certain ways, since they can allocate their vote as they wish in the privacy and security of the voting booth while maintaining the anonymity of the vote. Secret ballots are nearly universal in modern democracy, and considered a basic right of citizenship, despite the difficulties that they cause (for example the inability to trace votes back to the corresponding voters increases the risk of someone stuffing additional fraudulent votes into the system: additional security controls are needed to minimize such risks).

Corporate privacy refers to the privacy rights of corporate actors like senior executives of large, publicly traded corporations. Desires for corporate privacy can frequently raise issues with obligations for public disclosures under securities and corporate law.

Organizational[edit]

Government agencies, corporations, groups/societies and other organizations may desire to keep their activities or secrets from being revealed to other organizations or individuals, adopting various security practices and controls in order to keep private information confidential. Organizations may seek legal protection for their secrets. For example, a government administration may be able to invoke executive privilege[31] or declare certain information to be classified, or a corporation might attempt to protect valuable proprietary information as trade secrets.[29]Spiritual and intellectual[edit]

The earliest legislative development of privacy rights began under British common law, which protected "only the physical interference of life and property." Its development from then on became "one of the most significant chapters in the history of privacy law."[32] Privacy rights gradually expanded to include a "recognition of man's spiritual nature, of his feelings and his intellect."[32] Eventually, the scope of those rights broadened even further to include a basic "right to be let alone", and the former definition of "property" would then comprise "every form of possession—intangible, as well as tangible." By the late 19th century, interest in a "right to privacy" grew as a response to the growth of print media, especially newspapersPRISM is a code name for a program under which the United States National Security Agency (NSA) collects Internet communications from various US Internet companies.[1][2][3] The program is also known by the SIGAD US-984XN.[4][5] PRISM collects stored Internet communications based on demands made to Internet companies such as Google LLC under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 to turn over any data that match court-approved search terms.[6] The NSA can use these PRISM requests to target communications that were encrypted when they traveled across the Internet backbone, to focus on stored data that telecommunication filtering systems discarded earlier,[7][8] and to get data that is easier to handle, among other things.[9]

PRISM began in 2007 in the wake of the passage of the Protect America Act under the Bush Administration.[10][11] The program is operated under the supervision of the U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISA Court, or FISC) pursuant to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).[12] Its existence was leaked six years later by NSA contractor Edward Snowden, who warned that the extent of mass data collection was far greater than the public knew and included what he characterized as "dangerous" and "criminal" activities.[13] The disclosures were published by The Guardian and The Washington Post on June 6, 2013. Subsequent documents have demonstrated a financial arrangement between the NSA's Special Source Operations division (SSO) and PRISM partners in the millions of dollars.[14]

Documents indicate that PRISM is "the number one source of raw intelligence used for NSA analytic reports", and it accounts for 91% of the NSA's Internet traffic acquired under FISA section 702 authority."[15][16] The leaked information came to light one day after the revelation that the FISA Court had been ordering a subsidiary of telecommunications company Verizon Communications to turn over to the NSA logs tracking all of its customers' telephone calls.[17][18]

U.S. government officials have disputed some aspects of the Guardian and Washington Post stories and have defended the program by asserting it cannot be used on domestic targets without a warrant, that it has helped to prevent acts of terrorism, and that it receives independent oversight from the federal government's executive, judicial and legislative branches.[19][20] On June 19, 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama, during a visit to Germany, stated that the NSA's data gathering practices constitute "a circumscribed, narrow system directed at us being able to protect our people."[21]

NSA warrantless surveillance (also commonly referred to as "warrantless-wiretapping" or "-wiretaps") refers to the surveillance of persons within the United States, including United States citizens, during the collection of notionally foreign intelligence by the National Security Agency (NSA) as part of the Terrorist Surveillance Program.[1] The NSA was authorized to monitor, without obtaining a FISA warrant, the phone calls, Internet activity, text messages and other communication involving any party believed by the NSA to be outside the U.S., even if the other end of the communication lay within the U.S.

Critics claimed that the program was an effort to silence critics of the Administration and its handling of several controversial issues. Under public pressure, the Administration allegedly ended the program in January 2007 and resumed seeking warrants from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC).[2] In 2008 Congress passed the FISA Amendments Act of 2008, which relaxed some of the original FISC requirements.

During the Barack Obama Administration, the Department of Justice continued to defend the warrantless surveillance program in court, arguing that a ruling on the merits would reveal state secrets.[3] In April 2009 officials at the United States Department of Justice acknowledged that the NSA had engaged in "overcollection" of domestic communications in excess of the FISC's authority, but claimed that the acts were unintentional and had since been rectified.[

The privacy laws of the United States deal with several different legal concepts. One is the invasion of privacy, a tort based in common law allowing an aggrieved party to bring a lawsuit against an individual who unlawfully intrudes into his or her private affairs, discloses his or her private information, publicizes him or her in a false light, or appropriates his or her name for personal gain.[1] Public figures have less privacy, and this is an evolving area of law as it relates to the media.[2]

The essence of the law derives from a right to privacy, defined broadly as "the right to be let alone." It usually excludes personal matters or activities which may reasonably be of public interest, like those of celebrities or participants in newsworthy events. Invasion of the right to privacy can be the basis for a lawsuit for damages against the person or entity violating the right. These include the Fourth Amendment right to be free of unwarranted search or seizure, the First Amendment right to free assembly, and the Fourteenth Amendment due process right, recognized by the Supreme Court as protecting a general right to privacy within family, marriage, motherhood, procreation, and child rearing.[3][4]

Attempts to improve consumer privacy protections in the US in the wake of the May–July 2017 Equifax data breach, which affected 145.5 million US consumers, failed to pass in Congress

Defamation, calumny, vilification, or traducement is the communication of a false statement that harms the reputation of, depending on the law of the country, an individual, business, product, group, government, religion, or nation.[1]

Under common law, to constitute defamation, a claim must generally be false and must have been made to someone other than the person defamed.[2] Some common law jurisdictions also distinguish between spoken defamation, called slander, and defamation in other media such as printed words or images, called libel.[3]

False light laws protect against statements which are not technically false, but which are misleading.[4]

In some civil law jurisdictions, defamation is treated as a crime rather than a civil wrong.[5] The United Nations Human Rights Committee ruled in 2012 that the libel law of one country, the Philippines, was inconsistent with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as urging that "State parties [to the Covenant] should consider the decriminalization of libel".[6] In Saudi Arabia, defamation of the state, or a past or present ruler, is punishable under terrorism legislation.[7]

A person who defames another may be called a "defamer", "libeler", "slanderer", or rarely a "famacide".

The term libel is derived from the Latin libellus (literally "small book" or "booklet").

Stalking is unwanted and/or repeated surveillance by an individual or group towards another person.[1] Stalking behaviors are interrelated to harassment and intimidation and may include following the victim in person or monitoring them. The term stalking is used with some differing definitions in psychiatry and psychology, as well as in some legal jurisdictions as a term for a criminal offense.

According to a 2002 report by the U.S. National Center for Victims of Crime, "virtually any unwanted contact between two people that directly or indirectly communicates a threat or places the victim in fear can be considered stalking",[2] although in practice the legal standard is usually somewhat stricter.

The difficulties associated with defining this term exactly (or defining it at all) are well documented.[3]

Having been used since at least the 16th century to refer to a prowler or a poacher (Oxford English Dictionary), the term stalker was initially used by media in the 20th century to describe people who pester and harass others, initially with specific reference to the harassment of celebrities by strangers who were described as being "obsessed".[4] This use of the word appears to have been coined by the tabloid press in the United States.[5] With time, the meaning of stalking changed and incorporated individuals being harassed by their former partners.[6] Pathé and Mullen describe stalking as "a constellation of behaviours in which an individual inflicts upon another repeated unwanted intrusions and communications".[7] Stalking can be defined as the willful and repeated following, watching or harassing of another person. Unlike other crimes, which usually involve one act, stalking is a series of actions that occur over a period of time.

Although stalking is illegal in most areas of the world, some of the actions that contribute to stalking may be legal, such as gathering information, calling someone on the phone, texting, sending gifts, emailing, or instant messaging. They become illegal when they breach the legal definition of harassment (e.g., an action such as sending a text is not usually illegal, but is illegal when frequently repeated to an unwilling recipient). In fact, United Kingdom law states the incident only has to happen twice when the harasser should be aware their behavior is unacceptable (e.g., two phone calls to a stranger, two gifts, following the victim then phoning them, etc).[8]

Cultural norms and meaning effect the way stalking is defined. Scholars note that the majority of men and women admit engaging in various stalking-like behaviors following a breakup, but stop such behaviors over time, suggesting that "engagement in low levels of unwanted pursuit behaviors for a relatively short amount of time, particularly in the context of a relationship break-up, may be normative for heterosexual dating relationships occurring within U.S. culture."[9]

Psychology and behaviors

People characterized as stalkers may be accused of having a mistaken belief that another person loves them (erotomania), or that they need rescuing.[8] Stalking can consist of an accumulation of a series of actions which, by themselves, can be legal, such as calling on the phone, sending gifts, or sending emails.[10]Stalkers may use overt and covert intimidation, threats and violence to frighten their victims. They may engage in vandalism and property damage or make physical attacks that are meant to frighten. Less common are sexual assaults.[8]

Intimate partner stalkers are the most dangerous type.[1] In the UK, for example, most stalkers are former partners and evidence indicates that mental illness-facilitated stalking propagated in the media accounts for only a minority of cases of alleged stalking.[11] A UK Home Office research study on the use of the Protection from Harassment Act stated: "The study found that the Protection from Harassment Act is being used to deal with a variety of behaviour such as domestic and inter-neighbour disputes. It is rarely used for stalking as portrayed by the media since only a small minority of cases in the survey involved such behaviour."[11]

Psychological effects on victims

Disruptions in daily life necessary to escape the stalker, including changes in employment, residence and phone numbers, take a toll on the victim's well-being and may lead to a sense of isolation.[12]According to Lamber Royakkers:[10]

Stalking is a form of mental assault, in which the perpetrator repeatedly, unwantedly, and disruptively breaks into the life-world of the victim, with whom they have no relationship (or no longer have). Moreover, the separated acts that make up the intrusion cannot by themselves cause the mental abuse, but do taken together (cumulative effect).

Stalking as a close relationship

Stalking has also been described as a form of close relationship between the parties, albeit a disjunctive one where the two participants have opposing goals rather than cooperative goals. One participant, often a woman, likely wishes to end the relationship entirely, but may find herself unable to easily do so. The other participant, often but not always a man, wishes to escalate the relationship. It has been described as a close relationship because the duration, frequency, and intensity of contact may rival that of a more traditional conjunctive dating relationship.[13]Types of victims

Based on work with stalking victims for eight years in Australia, Mullen and Pathé identified different types of stalking victims dependent on their previous relationship to the stalker. These are:[6]- Prior intimates: Victims who had been in a previous intimate relationship with their stalker. In the article, Mullen and Pathé describe this as being "the largest category, the most common victim profile being a woman who has previously shared an intimate relationship with her (usually) male stalker." These victims are more likely to be exposed to violence being enacted by their stalker especially if the stalker had a criminal past. In addition, victims who have "date stalkers" are less likely to experience violence by their stalkers. A "date stalker" is considered an individual who had an intimate relationship with the victim but it was short-lived.[6]

- Casual acquaintances and friends: Amongst male stalking victims, most are part of this category. This category of victims also includes neighbor stalking. This may result in the victims' change of residence.[6]